He was born under the sultry skies of Bombay, spoke Hindi before English, and carried the rhythm of India into the pages of The Jungle Book that the world

would never forget.

Some birthdays deserve a bit of noise - not the loud, firecracker kind, but that quiet hum of recognition that travels through memory and literature. December 30 marks the birth of Rudyard Kipling, the man who gave us The Jungle Book - and curiously enough, a boy from Mumbai before he was anything else. Yes, Mumbai (then Bombay), the steamy, seductive chaos of it all, where the scent of coconut oil and sea salt makes its way into your dreams. That’s where it began.

Malabar Point, Bombay (1865) - where Kipling was born

The Boy Who Spoke Hindi Before English

Kipling’s earliest lullabies? They weren’t English nursery rhymes. They were Hindustani phrases murmured by his ayahs and servants - rolling, rhythmic, almost musical. He later admitted that he “came to English late,” which may explain why his sentences carry the cadence of translation, the heartbeat of two tongues speaking at once. One can almost imagine little Ruddy toddling around the compound, half in wonder, half sunburnt, with Hindi words shaping the fog of his thoughts.

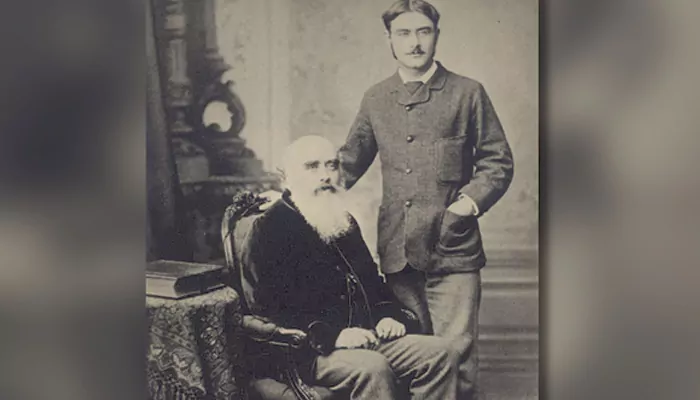

A young Rudyard Kipling with his father John Lockwood Kipling

Born in 1865 at the J. J. School of Art’s campus where his father, John Lockwood Kipling, was a professor, he was surrounded by artists and artisans. The Bombay of those days - not yet manicured into “Maximum City” - had texture: tram bells, cinnamon in the markets, the chants from temples blending with distant church bells. Perhaps that polyphony seeded his fascination with the many Indias he later wrote of - both lovingly and problematically.

Between Two Worlds

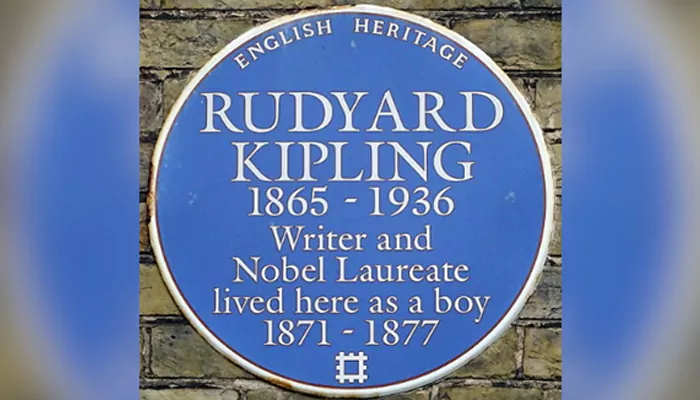

English Heritage blue plaque marking Kipling's time in Southsea, Portsmouth

Of course, Kipling is a complicated legacy. Some call him an imperial apologist; others see him as a tragic bridge between worlds. I’d say: both. He loved India, but he loved it as those who’ve left often do - romantically, from afar. When his family sent him to England at six, something inside him fractured. The boy who once spoke in Hindi lost his natural tongue bit by bit, replaced by the stern vowels of the British boarding school. Still, Bombay shadowed him - in his dreams, in Kim, in the dusty road adventures that felt unmistakably rooted in this place.

The Jungle Beckons

The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling

Then came The Jungle Book, written in the 1890s while he lived halfway across the world. Yet its pulse belongs to India - the monsoon-hushed jungles, the rustle of banana leaves, the flicker of torchlight on fur. Bagheera, Mowgli, even Baloo - they move not through imagined spaces but remembered ones. Kipling didn’t just write animals that talked; he wrote wildness itself, something both terrifying and tenderly familiar.

Strangely, though, one wonders - if little Ruddy hadn’t first learned to speak Hindi, to hear the rhythm of another land before his own - would The Jungle Book have felt so alive? Probably not.

The Legacy, Still Breathing

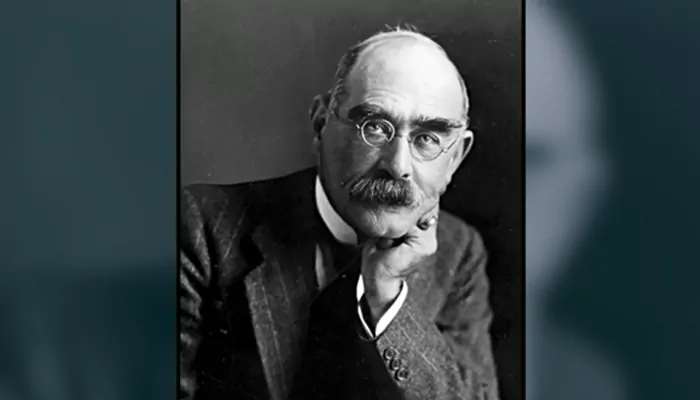

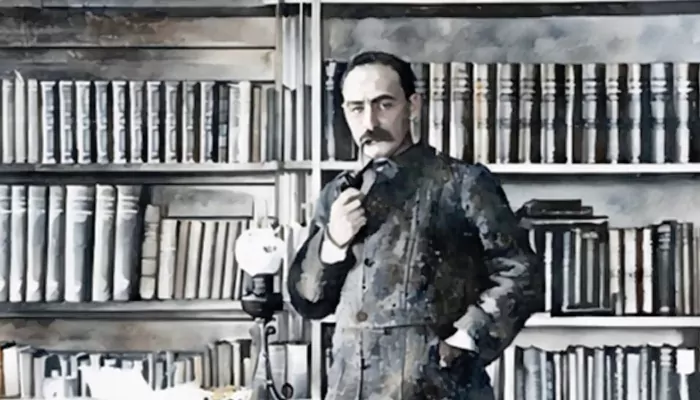

Rudyard Kipling: The Native Sahib

Even now, in the alleys of South Mumbai, there’s something ghostlike about him. Perhaps it’s nostalgia, perhaps it’s the charm of stories that outlive their tellers. Kipling remains one of literature’s most debated sons - adored, disputed, dissected - but never forgotten.

And on his birthday, maybe that’s the simplest tribute: to remember the boy who once said his first words in Hindi, and later taught the world to listen to the jungle’s quiet roar.