According to the report, officials familiar with early deliberations say New Delhi is considering seeking bids to build as many as ten pressurised heavy water reactors (PHWRs) of 700 MW each — marking the third time India will issue a bulk order for indigenous PHWRs.

Such a move would allow the government to negotiate better pricing and reduce construction risks through standardisation. With the Union Budget 2026–27 due on February 1, policy watchers expect this bulk order to be accompanied by industrial incentives to boost nuclear manufacturing and supply‑chain localisation.

The plan fits into a broader nuclear strategy that has shifted meaningfully over the past year. India has opened up its atomic sector to private companies under the SHANTI Act, passed in December, aiming to expand nuclear capacity to 100 gigawatts by 2047 — an eleven‑fold jump from 8.8 GW today. Government estimates place the required investment at roughly $211 billion.

Budget anticipation has therefore become central to the story. Reports suggest that tax incentives, PLI-style subsidies, and guaranteed procurement could accelerate capital mobilisation for the 100-GW goal.

SHANTI and the private-capital pivot

Context matters. Coal and renewables have expanded rapidly over the past decade, while nuclear and natural gas have lagged in India’s power mix. The December legislation eases liability terms that had previously deterred global vendors, and creates space for private and joint‑venture operators, while allowing up to 49% foreign investment.

Opposition parties have criticised exemptions for damages caused by natural disasters, armed conflict and terrorism, arguing that the changes favour US suppliers. The government maintains that the new framework aligns India with global norms and unlocks capital.

New Delhi’s nuclear push also comes at a time when electricity demand from AI workloads, data centres and green manufacturing is stretching existing capacity. Meanwhile, nuclear power is experiencing a global revival. Morgan Stanley expects global capacity to double to 860 GW by 2050, drawing $2.2 trillion in investment, with India seen as a meaningful contributor.

To date, the only foreign‑built units in India are at Kudankulam, where a longstanding agreement with Russia’s Rosatom predating the 2010 liability law enabled two gigawatt‑class VVERs, with four more under construction.

Government officials are framing the new regime as structural reform. Jitendra Singh, MoS for the Department of Atomic Energy, has called SHANTI a “landmark” that changes the sector’s “entire format”, enabling private participation akin to space‑sector reforms. Prime Minister Modi has positioned the shift as critical for clean energy, AI and energy security — and as vital to achieving developed‑nation status by 2047.

International signalling has followed. India discussed hybrid nuclear‑renewable systems with the IAEA at Davos, and NTPC joined the World Nuclear Association in January, reflecting growing industry confidence.

Budget incentives to unlock manufacturing

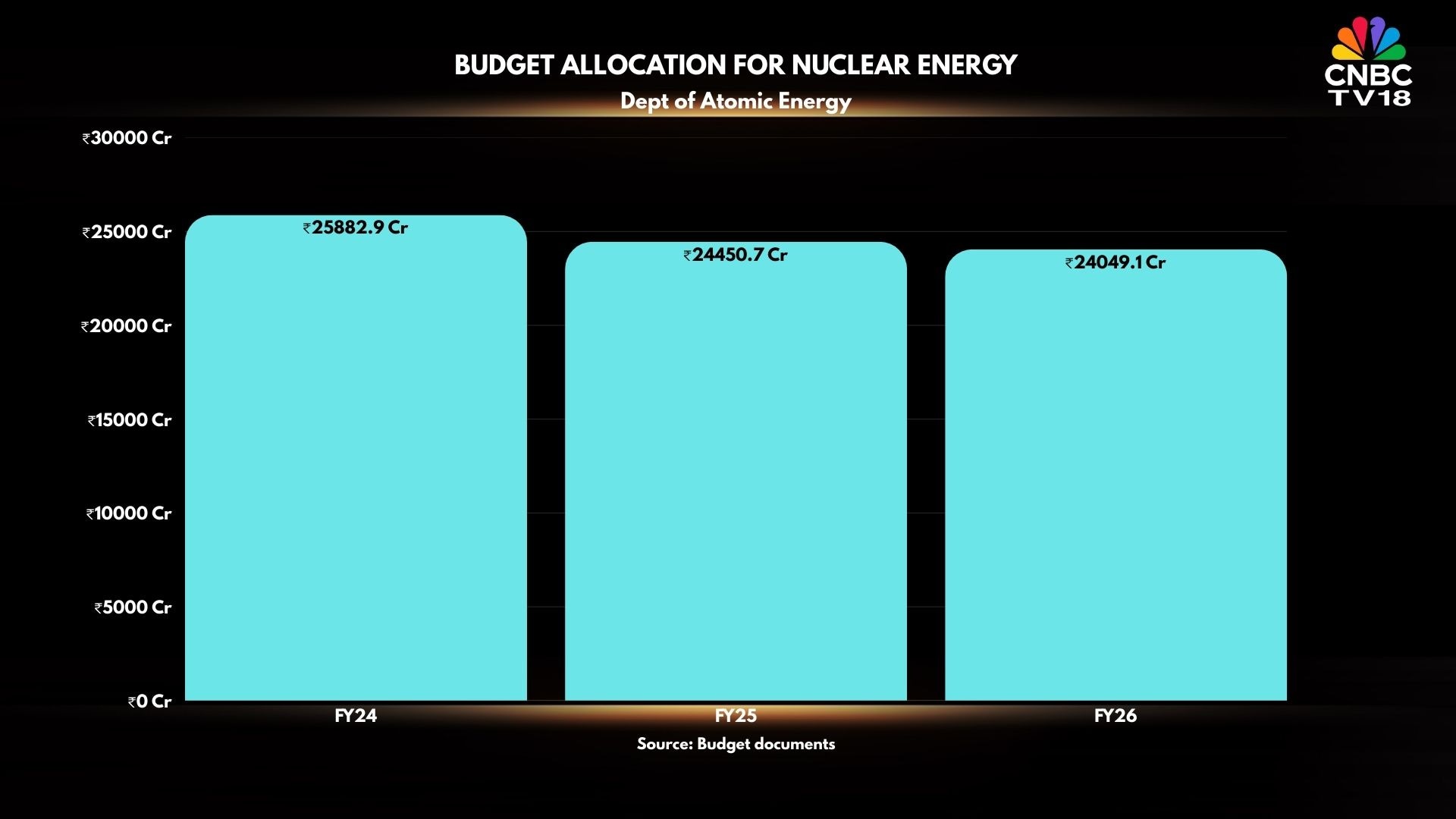

The budget allocation for the Department of Atomic Energy has seen a marginal decline over the past three years.

However, Budget 2027 could become the next catalytic step. Market reports indicate that the government is evaluating an ₹18,000–20,000 crore PLI scheme for reactor forgings, pressure vessels and nuclear‑grade alloys to localise supply chains and support the 100‑GW ambition. Officials say the incentives are also intended to prepare for small modular reactors, which require standardised manufacturing and a deeper vendor ecosystem. Policy discussions are ongoing, with inter‑ministerial consultations expected to shape the final contours.

If bulk ordering provides scale and visibility, and Budget 2027 delivers industrial and fiscal support, nuclear power could move from legislative reform to active execution. The key question now is whether a price‑sensitive electricity market, still dominated by coal and low‑cost solar, can absorb nuclear power at scale — and whether the state is prepared to bridge that gap through procurement, incentives and long‑term certainty.