What is the story about?

India’s economy will have to grow 7.5% for the 23 years to reach the World Bank’s high-income threshold of $13,936 in gross national income (GNI) per capita by 2047, according to the latest estimates by SBI Research, a unit of the country’s largest bank.

However, it’s important to note that the World Bank revises the thresholds annually to account for inflation and currency movements, meaning countries must not only grow, but grow faster than the global average to climb the income ladder.

The global distribution has changed dramatically over time. In 1990, the World Bank classified 51 countries as low-income and just 39 as high-income. By 2024, the number of low-income countries had fallen to 26, while high-income economies had risen to 87, the report highlighted.

If the threshold increases to around $18,000 per capita by 2047, India would need to sustain nearly 8.9% annual per capita income growth, implying about 11.5% nominal GDP growth in dollar terms, after accounting for population growth and global inflation.

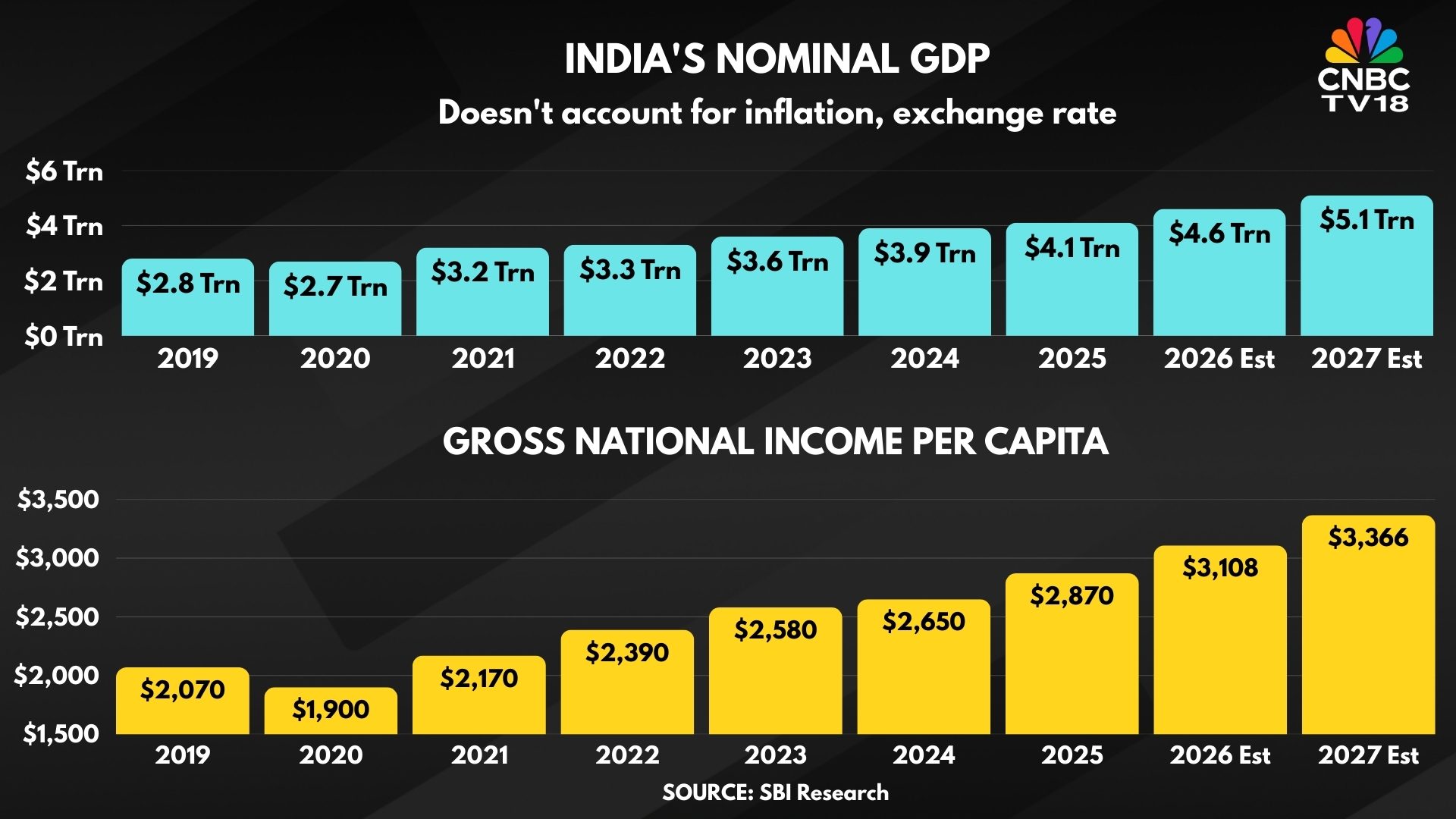

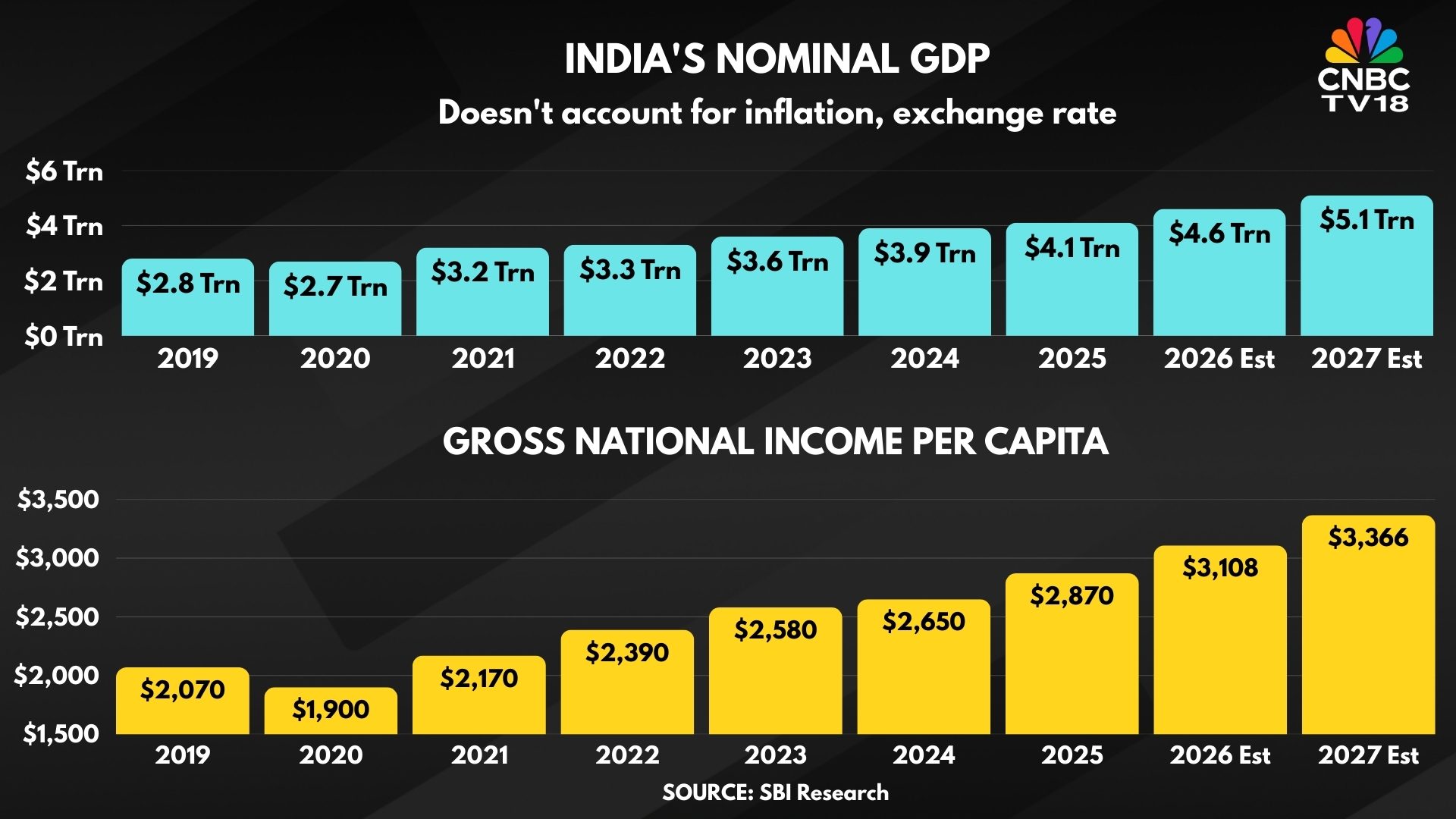

India’s nominal GDP has grown at a compounded annual rate of 7.8% since 2019. The estimated GNI per capita was $2,870 in 2025.

Longer-term trends support the projections as nominal GDP growth in dollar terms averaged close to 11% in the pre-pandemic period and about 10% over the past two decades, despite global shocks, the report added.

The good news is that the size of the Indian economy is projected to hit $5 trillion by 2027, according to a recent projection from NITI Aayog CEO BVR Subrahmanyam. That’s a commendable feat, albeit a couple of years later than the target set by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the height of the pandemic.

The pace of economic growth seems to have gained pace despite a faster fall in the value of the rupee, which has lost over a quarter of its value against the world’s reserve currency since 2019. A weakening rupee directly reduces the dollar value of India's economic growth.

Where does India stand in global growth rankings?

The World Bank classifies economies into four income groups based on GNI per capita:

Delivering this would require a shift beyond cyclical expansion to structural transformation, driven by higher productivity, a stronger manufacturing base, sustained private investment, and reform-led gains in incremental growth.

Therefore, achieving high-income status is feasible, but only if India can maintain consistently high nominal growth and avoid stagnation after entering the upper-middle-income bracket.

Neelkanth Mishra, Chief Economist at Axis Bank and Head of Global Research at Axis Capital has said that India’s economy could grow at 7.5% in FY27 as easing fiscal and monetary headwinds allow growth to move above its long-term trend.

India’s economy grew 6.5% in FY25 despite sharp policy headwinds, with fiscal consolidation of 130 bps and monetary tightening creating a drag of over 2% of GDP, Mishra said. In FY26, fiscal policy remains restrictive as the fiscal deficit is being reduced from 4.8% to 4.4%, and “the tax cuts were not a fiscal stimulus,” even as incremental monetary headwinds have largely faded.

Who else is in the Upper Middle-Income Club?

The global distribution has changed dramatically over time. In 1990, the World Bank classified 51 countries as low-income and just 39 as high-income. By 2024, the number of low-income countries had fallen to 26, while high-income economies had risen to 87, underscoring how sustained growth can reshape national income status over time

Several economies such as Thailand, Peru, Maldives, and Ukraine moved from lower middle-income to upper middle-income, while others like Uruguay, Hungary, and Russia climbed further into the high-income bracket

Guyana has emerged as the best-performing economy in SBI’s analysis of 48 low- and middle-income countries in 1990 that later moved up the income ladder, transitioning from a low-income country in 1990 to a high-income economy by 2024, with its per capita GNI surging more than 51-fold to $20,140 in 2024 from just $390 in 1990.

India currently sits in the lower middle-income category, but following its transition, it will join China and Indonesia at their current upper middle-income classification. China, which was a low-income country in 1990 with a per capita income of just $330, and Indonesia both moved into the upper middle-income bracket over the same period - a phase that India’s trajectory now increasingly mirrors as its income acceleration begins to compound.

Below is a snapshot of selected upper middle-income economies and their most recent GNI per capita in current USD. (This list is illustrative, not exhaustive.)

Where does the Indian economy currently stand?

In April 2018, the Indian government publicly articulated for the first time a clear nominal GDP target, with then Economic Affairs Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg saying India was expected to become a $5 trillion economy by 2025, supported by structural reforms such as GST, formalisation of the economy, and digitisation.

The ambition was reiterated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in June 2019 during the fifth Governing Council meeting of NITI Aayog, where he described the goal of making India a $5 trillion economy by 2024–25 as “challenging, but surely achievable.”

However, over time, this GDP-size ambition expanded into a longer-term vision. The economy is expected to achieve the $5 trillion milestone not before 2027 and earlier this month, NITI Aayog CEO B.V.R. Subrahmanyam said India should aim to build an $8–10 trillion export economy only by 2047.

Importantly, these goals were articulated in nominal U.S. dollar terms, meaning they do not adjust for inflation or account for currency movements, making GDP milestones sensitive not just to real growth but also to exchange-rate dynamics.

As India’s $5 trillion and $10 trillion GDP goals are expressed in nominal USD terms, they do not adjust for inflation or changes in the exchange rate, meaning that currency movements directly affect the dollar value of India’s GDP even if the economy grows in rupee terms.

Since late 2019, the Indian rupee has weakened more than 25% against the US, trading around roughly ₹71 per dollar in December 2019 and moving toward over ₹90 by early 2026, with occasional breaches above ₹91 as external pressures have mounted.

This erosion in the rupee’s value against the dollar reduces the dollar-measured size of India’s economy compared with where it would be if the exchange rate had remained stable, making attainment of nominal GDP targets harder even if real growth remains strong.

Can india reach the Upper Middle Income mark by 2030?

India’s transition to upper middle-income status by 2030 appears achievable if recent income and growth trends hold. According to SBI Research, India’s per capita GNI has grown at a CAGR of about 8.3% between 2001 and 2024, and at this pace, per capita income is projected to reach around $3,000 by 2026 and close to $4,000 by 2030.

The current World Bank threshold for classification as an upper middle-income country is $4,496 per capita, suggesting that India is within striking distance of the required level over the next five years.

SBI estimates that achieving this transition would require nominal GDP growth of roughly 11–11.5% in USD terms, after accounting for population growth of around 0.6% annually. India’s historical performance supports this assumption as nominal GDP growth in dollar terms averaged close to 11% in the pre-pandemic period and about 10% over the past two decades, despite global shocks.

Coupled with India’s position in the 95th percentile of global real GDP growth over the last decade, these trends suggest that crossing into the upper middle-income category by 2030 is a realistic, though execution-dependent, outcome.

What will it take for India to become a High-Income Country?

According to SBI Research, India can aspire to high-income country status by around 2047, but only if it sustains a demanding growth trajectory over the long term.

At today’s World Bank threshold of about $13,936 per capita, India’s per capita GNI would need to grow at a CAGR of roughly 7.5% over the next 23 years. This benchmark is not unrealistic given India’s per capita GNI is already growing fast at about 8.3% annually between 2001 and 2024. This indicates that the baseline requirement is achievable if momentum is maintained.

The challenge, however, lies in a moving goalpost. SBI cautions that if the high-income threshold rises to around $18,000 per capita by 2047, India would need to sustain nearly 8.9% annual per capita income growth, implying about 11.5% nominal GDP growth in dollar terms, after accounting for population growth and global inflation.

Delivering this would require a shift beyond cyclical expansion to structural transformation, driven by higher productivity, a stronger manufacturing base, sustained private investment, and reform-led gains in incremental growth. Therefore, reaching high-income status is feasible, but only if India can maintain consistently high nominal growth and avoid stagnation after entering the upper middle-income bracket.

However, it’s important to note that the World Bank revises the thresholds annually to account for inflation and currency movements, meaning countries must not only grow, but grow faster than the global average to climb the income ladder.

The global distribution has changed dramatically over time. In 1990, the World Bank classified 51 countries as low-income and just 39 as high-income. By 2024, the number of low-income countries had fallen to 26, while high-income economies had risen to 87, the report highlighted.

If the threshold increases to around $18,000 per capita by 2047, India would need to sustain nearly 8.9% annual per capita income growth, implying about 11.5% nominal GDP growth in dollar terms, after accounting for population growth and global inflation.

India’s nominal GDP has grown at a compounded annual rate of 7.8% since 2019. The estimated GNI per capita was $2,870 in 2025.

Longer-term trends support the projections as nominal GDP growth in dollar terms averaged close to 11% in the pre-pandemic period and about 10% over the past two decades, despite global shocks, the report added.

The good news is that the size of the Indian economy is projected to hit $5 trillion by 2027, according to a recent projection from NITI Aayog CEO BVR Subrahmanyam. That’s a commendable feat, albeit a couple of years later than the target set by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the height of the pandemic.

The pace of economic growth seems to have gained pace despite a faster fall in the value of the rupee, which has lost over a quarter of its value against the world’s reserve currency since 2019. A weakening rupee directly reduces the dollar value of India's economic growth.

Where does India stand in global growth rankings?

The World Bank classifies economies into four income groups based on GNI per capita:

| Category | Income threshold | Some countries in the group |

| Low-income | up to $1,135 | Afghanistan, Korea, Uganda, |

| Lower middle-income | $1,136 to $4,495 | India, Philippines, Cambodia |

| Upper middle-income | $4,496 to $13,935 | China, Mexico, Indonesia |

| High-income | above $13,935 | Finland, United Kingdom, United States |

Delivering this would require a shift beyond cyclical expansion to structural transformation, driven by higher productivity, a stronger manufacturing base, sustained private investment, and reform-led gains in incremental growth.

Therefore, achieving high-income status is feasible, but only if India can maintain consistently high nominal growth and avoid stagnation after entering the upper-middle-income bracket.

Neelkanth Mishra, Chief Economist at Axis Bank and Head of Global Research at Axis Capital has said that India’s economy could grow at 7.5% in FY27 as easing fiscal and monetary headwinds allow growth to move above its long-term trend.

India’s economy grew 6.5% in FY25 despite sharp policy headwinds, with fiscal consolidation of 130 bps and monetary tightening creating a drag of over 2% of GDP, Mishra said. In FY26, fiscal policy remains restrictive as the fiscal deficit is being reduced from 4.8% to 4.4%, and “the tax cuts were not a fiscal stimulus,” even as incremental monetary headwinds have largely faded.

Who else is in the Upper Middle-Income Club?

The global distribution has changed dramatically over time. In 1990, the World Bank classified 51 countries as low-income and just 39 as high-income. By 2024, the number of low-income countries had fallen to 26, while high-income economies had risen to 87, underscoring how sustained growth can reshape national income status over time

Several economies such as Thailand, Peru, Maldives, and Ukraine moved from lower middle-income to upper middle-income, while others like Uruguay, Hungary, and Russia climbed further into the high-income bracket

Guyana has emerged as the best-performing economy in SBI’s analysis of 48 low- and middle-income countries in 1990 that later moved up the income ladder, transitioning from a low-income country in 1990 to a high-income economy by 2024, with its per capita GNI surging more than 51-fold to $20,140 in 2024 from just $390 in 1990.

India currently sits in the lower middle-income category, but following its transition, it will join China and Indonesia at their current upper middle-income classification. China, which was a low-income country in 1990 with a per capita income of just $330, and Indonesia both moved into the upper middle-income bracket over the same period - a phase that India’s trajectory now increasingly mirrors as its income acceleration begins to compound.

Below is a snapshot of selected upper middle-income economies and their most recent GNI per capita in current USD. (This list is illustrative, not exhaustive.)

| Country | GNI per capita (US$) |

| Albania | ~9,910 |

| Algeria | ~5,370 |

| Argentina | ~13,530 |

| Armenia | ~7,810 |

| Azerbaijan | ~7,330 |

| China | ~13,660 |

| Indonesia | ~4,910 |

| Guyana | ~20,140 |

Where does the Indian economy currently stand?

In April 2018, the Indian government publicly articulated for the first time a clear nominal GDP target, with then Economic Affairs Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg saying India was expected to become a $5 trillion economy by 2025, supported by structural reforms such as GST, formalisation of the economy, and digitisation.

The ambition was reiterated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in June 2019 during the fifth Governing Council meeting of NITI Aayog, where he described the goal of making India a $5 trillion economy by 2024–25 as “challenging, but surely achievable.”

However, over time, this GDP-size ambition expanded into a longer-term vision. The economy is expected to achieve the $5 trillion milestone not before 2027 and earlier this month, NITI Aayog CEO B.V.R. Subrahmanyam said India should aim to build an $8–10 trillion export economy only by 2047.

Importantly, these goals were articulated in nominal U.S. dollar terms, meaning they do not adjust for inflation or account for currency movements, making GDP milestones sensitive not just to real growth but also to exchange-rate dynamics.

As India’s $5 trillion and $10 trillion GDP goals are expressed in nominal USD terms, they do not adjust for inflation or changes in the exchange rate, meaning that currency movements directly affect the dollar value of India’s GDP even if the economy grows in rupee terms.

Since late 2019, the Indian rupee has weakened more than 25% against the US, trading around roughly ₹71 per dollar in December 2019 and moving toward over ₹90 by early 2026, with occasional breaches above ₹91 as external pressures have mounted.

This erosion in the rupee’s value against the dollar reduces the dollar-measured size of India’s economy compared with where it would be if the exchange rate had remained stable, making attainment of nominal GDP targets harder even if real growth remains strong.

Can india reach the Upper Middle Income mark by 2030?

India’s transition to upper middle-income status by 2030 appears achievable if recent income and growth trends hold. According to SBI Research, India’s per capita GNI has grown at a CAGR of about 8.3% between 2001 and 2024, and at this pace, per capita income is projected to reach around $3,000 by 2026 and close to $4,000 by 2030.

The current World Bank threshold for classification as an upper middle-income country is $4,496 per capita, suggesting that India is within striking distance of the required level over the next five years.

SBI estimates that achieving this transition would require nominal GDP growth of roughly 11–11.5% in USD terms, after accounting for population growth of around 0.6% annually. India’s historical performance supports this assumption as nominal GDP growth in dollar terms averaged close to 11% in the pre-pandemic period and about 10% over the past two decades, despite global shocks.

Coupled with India’s position in the 95th percentile of global real GDP growth over the last decade, these trends suggest that crossing into the upper middle-income category by 2030 is a realistic, though execution-dependent, outcome.

What will it take for India to become a High-Income Country?

According to SBI Research, India can aspire to high-income country status by around 2047, but only if it sustains a demanding growth trajectory over the long term.

At today’s World Bank threshold of about $13,936 per capita, India’s per capita GNI would need to grow at a CAGR of roughly 7.5% over the next 23 years. This benchmark is not unrealistic given India’s per capita GNI is already growing fast at about 8.3% annually between 2001 and 2024. This indicates that the baseline requirement is achievable if momentum is maintained.

The challenge, however, lies in a moving goalpost. SBI cautions that if the high-income threshold rises to around $18,000 per capita by 2047, India would need to sustain nearly 8.9% annual per capita income growth, implying about 11.5% nominal GDP growth in dollar terms, after accounting for population growth and global inflation.

Delivering this would require a shift beyond cyclical expansion to structural transformation, driven by higher productivity, a stronger manufacturing base, sustained private investment, and reform-led gains in incremental growth. Therefore, reaching high-income status is feasible, but only if India can maintain consistently high nominal growth and avoid stagnation after entering the upper middle-income bracket.