The Hidden Danger Within

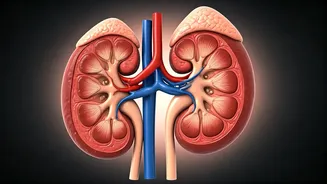

Oxalate, a naturally occurring substance, is usually processed and expelled by the body via urine. However, in individuals with hyperoxaluria, this efficient

removal process falters, leading to an accumulation of oxalate. This excess oxalate then binds with calcium, forming crystals that can gradually inflict damage on kidney tissues. This insidious process, often mistaken for common kidney stones, can silently progress, impairing kidney function without early warning signs. In advanced stages, the consequences can extend beyond the kidneys, potentially affecting other vital organs. Recognizing and addressing hyperoxaluria promptly is therefore paramount to safeguarding overall health and preventing irreversible organ damage.

Unpacking Metabolic Origins

Hyperoxaluria is fundamentally a metabolic disorder characterized by the body's excessive production or absorption of oxalate. This disruption in waste elimination pathways can have serious repercussions, particularly for the kidneys. The excess oxalate doesn't just sit idly; it actively combines with calcium, most commonly precipitating as calcium oxalate stones. These crystalline deposits are not mere inconveniences; they are agents of gradual injury to the delicate kidney structures. In primary hyperoxaluria, a genetic component is often at play, stemming from specific liver enzyme defects that trigger a relentless overproduction of oxalate from a very young age. This inherited form can be particularly challenging to diagnose early, as its initial symptoms often mimic those of more common kidney stone ailments, leading to delayed identification, especially in pediatric patients.

Spotting the Early Clues

The earliest indicators of hyperoxaluria frequently manifest as recurring kidney stones. Patients might experience intense, sharp pain in their back or abdominal region, notice blood in their urine, or suffer from discomfort and increased frequency during urination. The presence of recurrent urinary tract infections is also a commonly reported symptom, adding to the patient's distress. For children afflicted with the inherited variants of this condition, a different set of symptoms may emerge, including episodes of vomiting, challenges with feeding, and a noticeable slowdown in growth and development. These signs, while potentially indicative of other issues, warrant thorough investigation when they appear persistently.

When Kidneys Decline

The progressive accumulation of oxalate over time poses a significant threat to kidney health. Persistent deposits of these crystals can erode kidney tissue, progressively diminishing their capacity to filter waste. Research underscores that as the kidneys lose their ability to clear oxalate efficiently, the substance begins to build up in the bloodstream. This systemic spread is termed systemic oxalosis, and it can extend the damage to other crucial organs. Beyond the kidneys, bones, eyes, blood vessels, and the heart can become targets, leading to symptoms like bone pain, increased susceptibility to fractures, anemia, vision disturbances, and cardiovascular complications. This advanced stage highlights the systemic nature of the disorder when left unmanaged.

Identifying High-Risk Groups

Individuals who inherit faulty genes from both parents are at the pinnacle of risk for developing primary hyperoxaluria. Consequently, it is strongly advised that siblings of diagnosed patients undergo early medical evaluation to screen for the condition. Beyond genetic predisposition, those with chronic intestinal disorders are also considered vulnerable. Conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, syndromes that impair fat absorption, and past intestinal surgeries, including bariatric procedures, can substantially amplify the amount of oxalate absorbed from the digestive tract. Furthermore, dietary habits that include a high consumption of oxalate-rich foods, particularly when coupled with insufficient calcium intake, can exacerbate urinary oxalate levels in certain susceptible individuals. A personal or family history of kidney stones or unexplained kidney disease serves as a critical warning sign that necessitates further medical attention.

Strategies for Management

The cornerstone of hyperoxaluria management revolves around actively reducing oxalate levels, preventing the formation of stones, and preserving the remaining kidney function. A fundamental recommendation for all patients is to maintain a high fluid intake, which helps to dilute urine and thereby decrease the likelihood of crystal formation. For some individuals, targeted dietary adjustments aimed at limiting oxalate absorption from the gut can prove beneficial. In specific genetic subtypes of primary hyperoxaluria, vitamin B6 therapy has shown promise in moderating oxalate production. More recently, innovative RNA-interference-based treatments have emerged, which directly target oxalate synthesis in the liver, marking a significant advancement in therapeutic options for eligible patients.

Interventions and Treatments

When kidney stones caused by hyperoxaluria lead to obstructions or infections, medical interventions such as surgical or endoscopic procedures may be necessary to address these complications. In cases of advanced kidney failure, dialysis plays a role in managing metabolic waste products, though it is important to note that it does not fully eradicate oxalate from the system. For the most severe manifestations of primary hyperoxaluria, particularly when kidney function is extensively compromised, a combined liver and kidney transplantation is considered the definitive treatment. This complex procedure not only restores renal function but also corrects the underlying metabolic defect responsible for excessive oxalate production, offering the best chance for long-term recovery and improved quality of life.

The Power of Early Action

The trajectory of hyperoxaluria can be significantly altered through timely and proactive measures. Early diagnosis is not just beneficial; it is essential for preventing the irreversible damage that this condition can inflict on organs. Appropriate genetic counselling plays a vital role, particularly for families with a history of the disorder, enabling informed decisions and proactive screening. Sustained follow-up care is equally crucial, allowing medical professionals to monitor the condition, adjust treatment plans as needed, and intervene promptly if complications arise. By embracing early detection and consistent management, individuals can dramatically improve their outcomes and significantly reduce the long-term health consequences associated with hyperoxaluria.