Beyond the Name

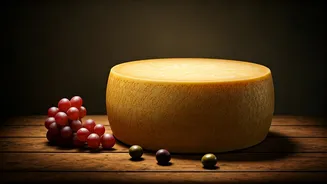

Have you ever felt a pang of disbelief or even indignation when encountering products like 'Turmeric Latte' or 'Naan Bread' in foreign markets, or perhaps

seen 'Indian Gruyere' or 'Indian Champagne' on supermarket shelves? This reaction mirrors what Italians, French, or Mexicans might feel upon seeing their cherished culinary identifiers applied to items that don't originate from their ancestral lands. While culinary innovation and the global spread of diverse flavors are commendable, the question arises: what truly qualifies a bubbly drink to be labelled 'Champagne,' or a specific cheese to be called 'Gruyere' or 'Parmigiano Reggiano'? The answer often lies in stringent geographical qualifications. For instance, genuine Champagne must hail from grapes grown in the Champagne region of France. Similarly, Tequila, while producible outside the Mexican state of Jalisco, is restricted to specific municipalities in a few other states and must be made from Blue Weber agave. If these criteria aren't met, such spirits are more accurately termed 'agave spirits' or 'mezcal,' highlighting the importance of origin and specific production methods in defining a product's identity.

Unveiling GI Tags

The concept of Geographical Indication (GI) tags is crucial in understanding product authenticity. These tags serve as a mark of origin, guaranteeing that a product originates from a specific geographical area and possesses qualities or a reputation due to that origin. This system came into sharp focus when Odisha sought a GI certificate for its rosogolla, a sweet dessert. Odisha asserts that its version, the 'khiramohana,' was first created as a sacred offering within its borders to Lord Jagannath. However, West Bengal presents a competing claim. Ultimately, in 2019, the 'Odisha Rasagola' received a GI tag, while West Bengal's softer, sponge-like white rasgulla had already secured its own separate GI tag in 2017. This duality underscores that even within a shared culinary heritage, distinct regional variations can and should be recognized and protected through these official designations.

A Flourish of Indian Delicacies

The rasgulla is far from being the sole Indian delicacy to benefit from GI tag recognition; indeed, recent years have witnessed a remarkable surge in such accolades. In 2022 and 2023 alone, a diverse array of products were granted GI status. These include the nutrient-rich Mithila Makhana from Bihar, the distinctive Tandur Red Gram from Telangana, and the unique Raktsey Karpo Apricot from Ladakh. Maharashtra's Alibag White Onion also earned its GI tag, as did Goa's prized Mancurad Mango. This wave of recognition highlights the rich tapestry of India's regional culinary heritage, bringing well-deserved attention to products that have been cultivated and prepared using traditional methods for generations. These tags not only celebrate local produce but also provide economic advantages and protect against imitations.

Icons of Indian GI

Beyond the recent additions, India boasts a venerable list of well-established GI-tagged food items that are celebrated nationwide and often internationally. Among these celebrated products are the globally renowned Darjeeling Tea from West Bengal, prized for its distinct muscatel flavor, and the highly sought-after Kashmir Saffron, known for its intense aroma and color. Nagaland contributes its fiery Naga King Chilli, one of the world's hottest peppers. From Rajasthan, the crispy Bikaneri Bhujia offers a popular savory snack. Andhra Pradesh's Tirupati Laddu is a famous temple offering, while Karnataka's Dharwad Peda is a beloved traditional sweet. Goa features its unique Goan Bebinca and the exquisite Alphonso Mango. Maharashtra also proudly claims the Alphonso Mango. Other notable inclusions are the aromatic Basmati Rice from northern regions, the visually striking Manipuri Black Rice, the semi-hard Kaladi Cheese from Jammu, reminiscent of Halloumi, and Odisha's Magji Laddoo. This extensive list demonstrates the vast diversity and depth of India's culinary landscape.

Sweet Triumphs from Bengal

The year prior saw several exquisite Indian sweets garnering GI tags, with a notable concentration from West Bengal, a state renowned for its masterful use of 'chhena' (freshly made paneer) and jaggery. First among these celebrated sweets is the Nolen Gur-er Sandesh. This delicacy is crafted from fresh chhena and slowly cooked with liquid date palm jaggery, known as 'nolen gur,' which is specifically harvested from date palms in the Bardhaman region of West Bengal. It is this unique jaggery that imparts the Sandesh its characteristic biscuit hue and a delightful caramelly sweetness, making it a truly distinctive confection. Another noteworthy recipient is the Murshidabad Chhanabora, also originating from West Bengal. This sweet involves shaping fresh chhena into small spheres, lightly frying them, and then immersing them in sugar syrup. The result is a treat with a subtly chewy interior and a caramelized exterior, often enhanced with fragrant cardamom or rose water, hinting at historical Mughal culinary influences in Bengal.

More Bengali Gems

Continuing the spotlight on West Bengal's sweet achievements, the Bishnupur Motichoor Laddoo, hailing from the historic temple town of Bishnupur in the Bankura district, is another exceptional creation. Unlike typical motichoor laddoos made from gram flour, these are crafted from tiny 'motichoor' pearls derived from the seeds of the piyal, or Indian almond tree. These delicate pearls are meticulously deep-fried in ghee, then infused with the aroma of freshly ground cardamom, and finally shaped by hand into soft, melt-in-your-mouth laddoos. The origins of these laddoos can be traced back to the Malla dynasty, a powerful ruling house in Bengal for over a millennium. Furthermore, the Kamarpukur Sada Bonde, originating from the village of Kamarpukur, presents another delightful sweet. These are described as pale, airy spheres of deep-fried sweet batter, made from a lightly flavored wheat-flour mixture. Fried to a crisp exterior while remaining soft inside, they are then briefly soaked in sugar syrup. Slightly larger than individual boondi pearls, these are savored as distinct sweets.

A Touch of Tamil Nadu

The sole non-Bengal recipient of a GI tag in this particular group of sweets is Kavindapadi Nattu Sakkarai from Tamil Nadu. This is a traditional form of jaggery produced from fresh sugarcane juice, which is slowly simmered over a wood fire. This artisanal jaggery is highly valued for its rich mineral content, including significant amounts of iron, magnesium, potassium, and calcium. It is characterized by its deep golden color and an inviting caramel aroma. The production of Kavindapadi Nattu Sakkarai has been a generational practice, meticulously carried out by local farmers in the Kavindapadi region for centuries, preserving a culinary heritage passed down through time and maintaining its unique regional identity.

The Essence of Authenticity

The overarching lesson from the proliferation of GI tags is clear: true authenticity and the right to use a specific name are intrinsically linked to heritage and localized, traditional knowledge. It is fundamentally incorrect to take an ingredient like Bengal's 'Nolen Gur,' a distinct liquid date palm jaggery, and mislabel it as 'Kavindapadi Nattu Sakkarai' simply because both are types of liquid jaggery. Similarly, a cheese that merely mimics the taste and aroma of Parmesan is not, by definition, Parmesan. These distinctions are vital. As Shakespeare poetically mused, 'What's in a name?' While he suggested a rose by any other name would smell as sweet, the advent of GI tags demonstrates that for many culinary products, the name is inextricably tied to their origin, history, and unique production methods. Therefore, when encountering a product, especially a traditional delicacy, it's perfectly acceptable, and indeed important, to inquire about its specific antecedents and ensure its claimed identity is genuine.