In the early 1970s, the U.S. Air Force, one of the largest air forces in the world, tasked Boeing with exploring an idea that sounded like pure science fiction: turning its brand-new 747 jumbo jet into a flying aircraft carrier. Officially known as the 747 Airborne Aircraft Carrier (AAC), this mobile airbase would carry, launch, refuel, and rearm a fleet of up to ten specially designed "microfighters" while in flight. This wasn't the first time the military had pursued such a vision. Decades earlier,

airborne carrier experiments had been attempted with massive rigid airships like the USS Akron and Macon, which deployed biplane scouts using a trapeze mechanism. Later, in the 1950s, the B-36 "FICON" program tested the idea of launching and recovering a jet fighter from a strategic bomber's bomb bay.

The U.S. saw this as a way to get combat aircraft deep into hostile territory far faster than traditional naval carriers or overseas airbases could manage. Once in position, the 747 AAC could release its fighters in around 15 minutes, provide them with multiple in-flight refuels, and retrieve them after their missions. This flying fortress would not just project power quickly but sustain it, thanks to the 747's massive payload capacity and long endurance.

The U.S Air Force looked at two possible mothership candidates for the AAC experiment: Lockheed's C-5A Galaxy heavy transport and the passenger plane we know as the Queen of the Skies — the Boeing 747. While Lockheed's transport offered easier structural modifications, Boeing's jet promised better speed, altitude performance, and range, all crucial for surviving in hostile skies. On paper, the AAC was technically feasible, but as history would prove, even the most futuristic designs face hard limits.

Read more: 10 Terrifying War Drones That Give Us Chills

How Boeing Planned To Launch And Recover Microfighters Mid-Flight

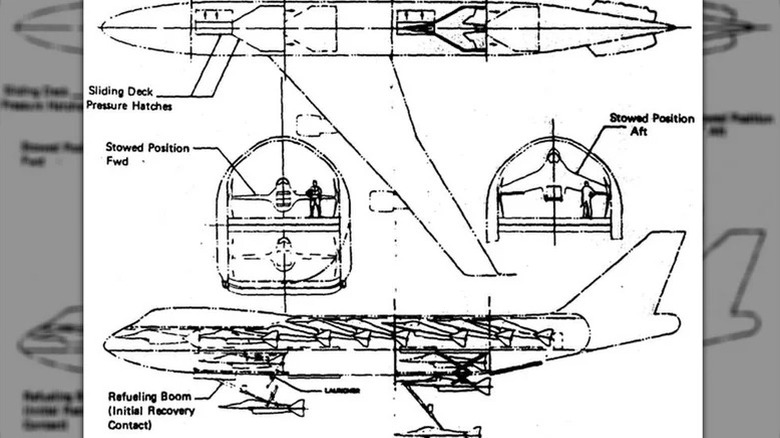

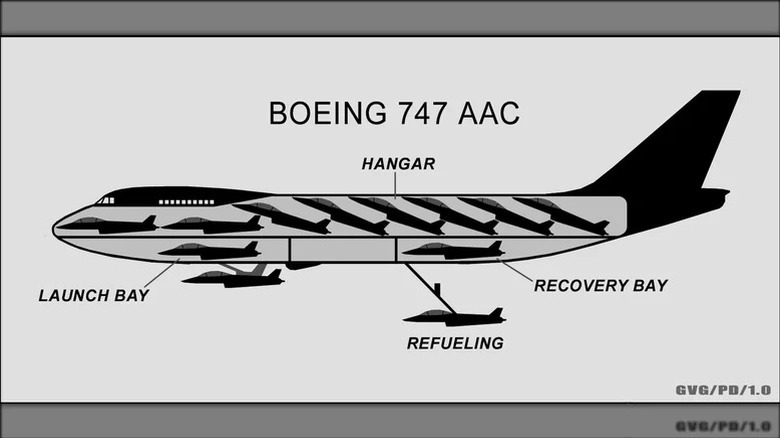

Boeing's 747 AAC design was both an engineering puzzle and a military dream. Inside its huge interior, the ten microfighters would be stored in a stacked formation, each small enough to fit within the jet's width restrictions yet powerful enough to perform interception and strike missions. To manage them, the AAC would use two pressurized launch and recovery bays, one at the front and one at the back, that worked as airlocks between the fighter hangar and the frigid air at high altitude.

Deployment would rely on a conveyor system feeding fighters into position, releasing two every 80 seconds. Recovery was even more complex: a fighter would first connect with a refueling boom extended from the carrier, which then guided it into a special docking system that locked it into place. Once secured, the fighter's engine would shut down, and the system would pull it back inside for refueling, rearming, or maintenance. Boeing estimated each turnaround would take about ten minutes per aircraft.

Supporting these operations required a 44-person crew: 12 to operate the carrier itself, 14 pilots for the microfighters, and 18 specialists for logistics, refueling, and weapons handling. The fighters themselves, designed under the Boeing Model 985 program, had to meet demanding criteria: compact 17.5-foot wingspans, single afterburning turbofan engines, basic cannon and missile armament, and enough performance to challenge Soviet interceptors. After testing small-scale models in wind tunnels, two designs were picked as the best candidates: a simple delta-wing fighter for easier construction, and a variable-sweep wing fighter that could adjust its wing position for better performance at different speeds.

Why The 747 AAC Never Took Off, And How Its Legacy Shapes Today's Airborne Carrier Concepts

Boeing's flying carrier faced too many obstacles to ever leave the drawing board. The biggest challenge was the fighters themselves, making them small enough to fit inside the 747 without compromising speed, weapons, or range proved nearly impossible. A microfighter that was too light risked being destabilized by turbulence during docking. Even if perfected, these aircraft would still be at a disadvantage against full-size fighters like the Soviet MiG-25, one of the most advanced Russian fighter jets of all time.

There were also risks in the carrier concept itself. A single accident could destroy the mothership and all fighters inside, along with their crews. The conveyor, docking, and refueling systems, all untested at this stage, added layers of complexity. Meanwhile, changes in warfare were making the idea less relevant. By the late 1970s, long-range surface-to-air missiles had become a bigger threat to bombers than enemy fighters, and the U.S was secretly developing stealth technology that would allow aircraft to bypass defenses altogether.

The 747 AAC was quietly shelved, but the idea never completely disappeared. In recent years, the U.S military has revived the airborne carrier concept in a new form, unmanned drones. DARPA's "Gremlins" program aims to launch and recover swarms of reusable drones from transport aircraft like the C-130, giving commanders flexible strike and surveillance capabilities without risking pilots. It's a far cry from Boeing's vision of a skyborne battle group, but the core ambition remains intact. The 747 AAC never flew, yet its blueprint continues to influence how the military imagines projecting air power in the future.

Want the latest in tech and auto trends? Subscribe to our free newsletter for the latest headlines, expert guides, and how-to tips, one email at a time.

Read the original article on SlashGear.