By Gwladys Fouche

OSLO (Reuters) -Unnerved by the Ukraine war and U.S. President Donald Trump's whiplash statements on defending Europe, Norway could allow its $2.1 trillion sovereign wealth fund, the world's largest, to invest in major defence companies from 2027 after a more than 20-year hiatus.

Such a move would enable the fund to take stakes in 14 defence companies with a combined market capitalisation of about $1 trillion, and which it cannot currently invest in under ethical guidelines because

they make components of nuclear weapons.

On November 4, parliament voted in favour of reviewing the fund's ethical guidelines, in place since 2004.

The companies that could become open to the fund are: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Airbus, BAE Systems, Safran, Thales, BWX Technologies, Northrop Grumman, Fluor, General Dynamics, Huntington Ingalls Industries, Jacobs Solutions, L3Harris Technologies and L&T.

Once spurned by ESG-minded investors, defence stocks are becoming more acceptable, as Russia continues to wage war in Ukraine, and European countries hike defence spending under pressure from the Trump administration.

The new security environment has also made defence stocks a potentially lucrative investment.

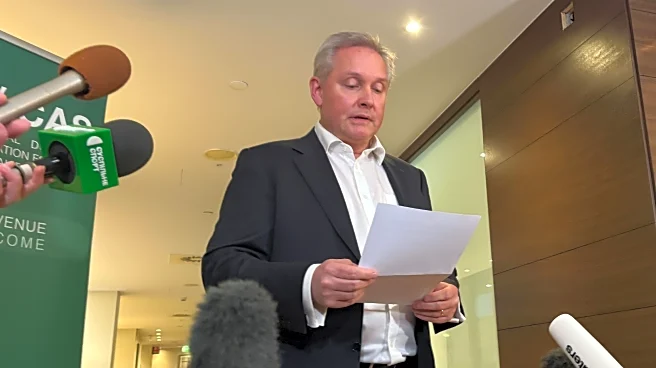

"Freedom is more important than ESG," Knut Kjaer, the fund's founding CEO, who served between 1998 and 2007, told Reuters. "Europe has to defend itself from the aggression from Russia. Why should we not invest in weapons?"

Norway was buying arms from the very same companies it has forbidden its fund from investing in, he said.

NORWAY'S FUND HAS SET INVESTING TRENDS

Any changes to the fund's guidelines could see other ESG-minded investors follow suit, such as when in 2016, it decided to shun companies that derive 30% of revenues from coal.

Last Friday, Norway's finance ministry named a commission to review the guidelines and which will make recommendations in October 2026, to be voted on in parliament in June 2027.

A NEW GLOBAL SECURITY SITUATION PROMPTS A RETHINK

Like Kjaer, the government has highlighted it is already a direct customer of many of these defence companies.

"On the one hand, we consider it ethically acceptable to transfer large sums to such (defence) companies as payment, while we consider it is unethical to receive much smaller amounts as returns from the same companies," Finance Minister Jens Stoltenberg, an ex-NATO chief, told parliament on October 24.

In the commission's mandate, the finance ministry highlights a "dilemma": Norway buys fighter jets from Lockheed and frigates from BAE Systems, yet 20 years ago agreed its wealth fund would not invest in them.

"Since then, both companies' involvement in weapons production and the security policy situation have changed. Nuclear weapons are fundamental to NATO's deterrence strategy, of which Norway is a part," it continued.

The minority Labour government would have the backing of enough parties to support a change to the guidelines.

"We can dislike nuclear weapons but it is a part of NATO's strategy and we are a NATO member. So it is hard to see the logic in not being able to invest," Hans Andreas Limi, the parliamentary leader for the second-largest party, Progress, told Reuters.

The third largest party, the Conservatives, is also supportive. Its incoming leader, Ine Eriksen Soereide, proposed such a change earlier this year.

Asked whether the government already backed a change ahead of the commission's recommendations, Deputy Finance Minister Ellen Reitan said the ministry would not comment beyond what had already been communicated in the mandate.

Not everyone agrees that a fund whose aim is to safeguard future generations of Norwegians should invest in companies that help produce weapons of mass destruction threatening the survival of humanity.

"We have ... heard it is a paradox that Norway cannot invest in companies we otherwise trade with. Is it really? Is there really no big difference between buying equipment our country needs and, for example, investing in nuclear weapons?," asked Kirsti Bergstoe, the leader of the Socialist Left party, in parliament on October 23.

DIVESTMENTS ON ETHICAL GROUNDS HAVE BEEN PAUSED

Norway, a NATO country of 5.6 million, is not part of the European Union and shares a border with Russia in the Arctic.

A former head of the fund's ethics watchdog, the body that issues recommendations on stocks to divest from the fund, says the ethical guidelines had to change to reflect events.

"We should be able to rework the ethical guidelines to say that 'we are in a pre-war period, or an inter-war period, and so we have to look at these weapons exclusions in another manner'," Ola Mestad, head of the Council on Ethics from 2010-2014, told Reuters.

That means, too, that Norway must tread more carefully when it issues ethical decisions to divest from international companies because the backlash can be more damaging than before, analysts said. Last week parliament paused such divestments.

"In the new regime of more politicised markets, we must be more aware of where we can be diluted, capital controls being introduced, have our assets confiscated, or being used as part of a weaponising of financial transactions where we may have to wait 100 years for getting our return back," said Kjaer.

Some 52.4% of the fund's assets, or $1 trillion, is invested in the U.S. across stocks, bonds and real estate.

In September, the U.S. State Department said it was "very troubled" by the decision to divest from Caterpillar over the use of its products by Israeli authorities in Gaza and the occupied West Bank.

(Reporting by Gwladys Fouche in Oslo; Editing by Alexandra Hudson)