Jan 28 (Reuters) - Scientists have unearthed in southern China fossils of a multitude of marine creatures dating to more than a half billion years ago, showing a deep-water ecosystem thriving in the aftermath of the first mass extinction of the animal world.

The Cambrian Period fossils, about 512 million years old, are of invertebrates of various shapes and sizes, including an apex predator with menacing grasping appendages. They are exceptionally well-preserved sometimes down to the cellular level,

revealing legs, gills, guts, eyes and even nerves.

The researchers collected more than 50,000 fossil specimens in mudstone from a single quarry, representing a highly diverse assemblage of organisms they call the Huayuan biota, named after the county in Hunan province where it is located. They examined a sample of 8,681 specimens and recognized 153 species - 91 of which were previously unknown - from 16 major animal groups.

The fossils date to a time when animal and plant life was still confined to the seas. They rival two other important fossil assemblages in providing a look at life in the Cambrian seas - the Burgess Shale biota of Canada's province of British Columbia and the Chengjiang biota of China's Yunnan province.

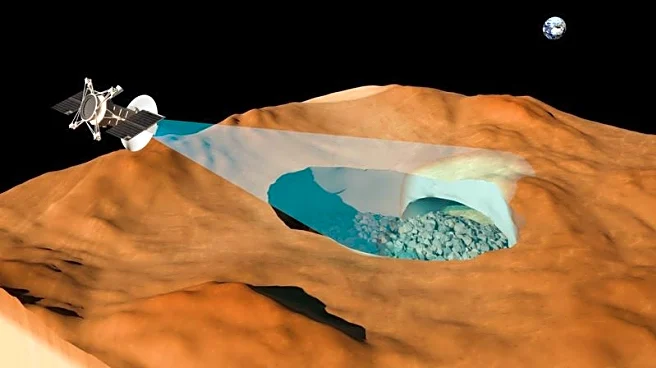

"The Huayuan biota was situated at a deep-water environment at the edge of the continental shelf of South China," said Han Zeng, a paleontologist at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and lead author of the study published on Wednesday in the journal Nature.

"The Huayuan biota was a thriving ecosystem with animals distributed from the water column to the surface and inside of marine sediment. The animals have various feeding habits and motility," Zeng said.

The dominant groups among the fossils included: arthropods, the group that includes today's crabs, shrimp, scorpions, insects, spiders, centipedes and millipedes; cnidarians, which include today's jellyfish, corals and sea anemones; and sponges, which are among the oldest animals.

The top predators were several members of a group of primitive arthropods called radiodonts that had raptorial appendages - specialized limbs to grab prey while swimming through the sea. Another creature was covered with spines and looked vaguely like a cactus.

While the animals discovered were all invertebrates, the Huayuan biota does include diverse and abundant members of a subdivision of animals considered the closest relatives of vertebrates.

The Huayuan fossils provide the best view yet of a marine ecosystem in the aftermath of a mass extinction called the Sinsk event that occurred about 513.5 million years ago, thought to have been caused by volcanism that triggered rapid global climate change. This mass extinction interrupted a burst of evolution called the Cambrian explosion when nearly all the major groups of the animal kingdom had first emerged.

"The Huayuan biota provides the first insights into the impact of the Sinsk event on deeper-water faunas," said paleontologist and study senior author Maoyan Zhu of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology.

The fossils indicate that the mass extinction did not hit deeper-water creatures as hard as their shallow-water counterparts, Zhu said.

The Burgess Shale animals date to about 508 million years ago, further removed from the Sinsk event than the Huayuan biota. Despite the vast distance separating the two sites, fossils of several of the same animals were found in the two locations.

"It surprised us when we found the Huayuan biota shared various animals with the Burgess Shale, including the arthropods Helmetia and Surusicaris that were previously only known from the Burgess Shale," Zeng said.

"As larval stages are common in extant marine invertebrates, the best explanation of these shared taxa shall be that the larvae of early animals were capable of spreading by ocean currents since the early days of animals in the Cambrian," Zeng said.

(Reporting by Will Dunham in Washington; Editing by Daniel Wallis)