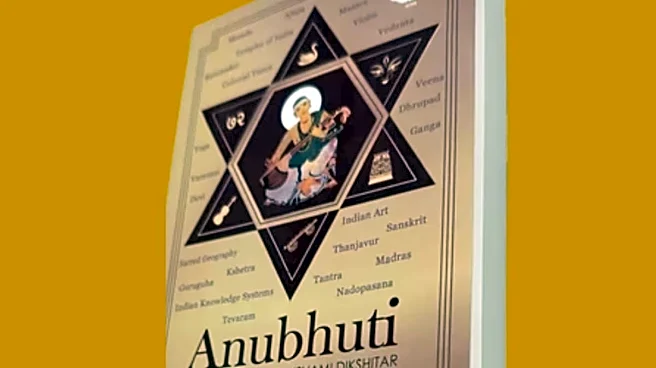

Dr Kanniks Kannikeswaran, a pioneer in Indian American choral music, brilliantly presents the life and contributions of the legendary composer and singer, Shri Muthusvāmi Dīkshitar (in some sense, the Bach of the East), through his Anubhūti. From the opening chapters introducing the basics of music, Kanniks guides us with vivid clarity through a chronology of Dīkshitar’s life — his early years, his teacher-learner relationships, the uniqueness of his musical output, his temple learning, his musical pilgrimages, his spiritual philosophy, his colonial interlude, etc. “A simplistic description of Dīkshitar’s kritis would be to state that they are essentially mantras delivered through the medium of music,” says Kanniks. The richly textured content

succeeds in keeping the reader engaged with gracefully woven stories from the lives of great incarnations, saints, personalities, and legends.

As a contextual backdrop to why Dr Kannikeswaran is the ideal person to write this material, the author has generously poured his expansive wealth of knowledge in music, temples, and his own lifelong creative journey into dialogue with Dīkshitar’s.

As a composer-educator, the author has spent more than three decades building Indian American community choirs, cultivating a “new sound” of raga-based ensemble music in the U.S., inspiring thousands of singers, and founding choirs in over a dozen cities.

His flagship, first-of-its-kind oratorio Shānti – A Journey of Peace merged Indian classical and Western choral traditions, reimagining Sanskrit chants and ragas for large mixed choruses and orchestras. Most recently, his Eagai was a resounding success with hundreds of performers and thousands of captivated spectators celebrating a symphony of Tamil — its spirituality, its culture, and its ethic of giving and sharing.

Furthermore, this book is not a standalone work on Dīkshitar by Kanniks. The author has published multiple articles on Dīkshitar, beginning as early as 2007, including his doctoral dissertation. Across all these and more such works, Kanniks has graciously infused Dīkshitar’s contributions, culminating now in this concentrated, focused, one-stop resource for everything about this Dīkshitar. Despite its eloquent and scholarly richness, the text would comfortably connect with and befriend any reader with little or no technical background.

Among the six principal factors, Kanniks identifies as contributing to the uniqueness of Dīkshitar’s musical (and lyrical) output, two stand out to me. The first is Dīkshitar’s colonial-era compositions. Dīkshitar was a perfect traditionalist and simultaneously an innovative, modern, international musical pioneer. The Note-svaras (Nottusvaras) are his carefully composed, creative fusions of popular Western melodies with Sanskrit lyrics. The Nottusvaras feel natural and cohesive, despite the absence of the microtones and ornamentation characteristic of Indian music, says Kanniks. If you are curious about the ragas and scales they map to, read the dedicated chapter on colonial encounters and reinterpretations of these European tunes into beautifully flowing Sanskrit songs. You may even recognise the original melodies—and find yourself humming the Sanskrit versions too, a delightful surprise for friends and family!

The second unique and transcendental aspect is Dīkshitar’s connection with Advaita (Non-duality; Non-otherness). Advaita is regarded as the final frontier in this Vedāntic tradition. Although there is not any object to gain or attain, for the sake of human understanding, it may be explained as the inexpressible, highest state—our Ever-present, Unchanging Reality.

Such a Knower of Brahman is not a mere individual but one who is beyond all descriptions, all boundaries of identity, form, space, time, causation, etc. The nineteenth-century Advaitin and Saint-Incarnate, Shri Rāmakrishna Paramahamsa, said that those who realise Brahman in samādhi also come down and find that it is That same Brahman that has become the universe and its living beings. He also said that in the musical scale, there are the notes sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, and ni; but one cannot hold one’s voice on “ni” for a very long time. Similarly, the ego does not vanish completely.

The individual coming down from samādhi perceives that it is the same Brahman that has become the ego, the universe, and all beings. This realisation is known as Vijnāna, said the Paramahamsa.

The Upanishads are the available ultimate source of That inscrutable Supreme Knowledge. The Sāma Vedic Chāndogya Upanishad also extols the greatness of singing — Udgītha and Pranava (Om/Aum). It is fortunate that Dīkshitar consistently espoused these aspects in his body of work—both Nirguna Brahman and Saguna Brahman. It is even more fortunate that Kanniks devotes several pages to Dīkshitar’s Advaitic orientation. That Dīkshitar studied Advaita under the tutelage of the great Upanishad Brahmyogin (Brahmam or Brahmendra) is a great blessing to all of us.

The latter’s contributions via his commentaries on the 108 Upanishads are invaluable even today for spiritual seekers across the world. Kanniks cites multiple compositions in which the Upanishadic Mahāvākya, “Tat Twam Asi” (“You are That”) shines through.

He highlights how Dīkshitar skillfully sprinkled this Advaitic metaphysical insight into various works with phrases such as “Sakalam Brahma Mayam”, “Māye Tvam Yāhi”, “He Māye Mām Bādhitum”, “Smaranāt Kaivalyaprada”, “Advaita Pratipādyam”, “Nirvikalpa Samādhi Nishtha Śiva Kalpataro”, “AkhaNda Saccidānandam”, “Paramādvaita Svātmānanda RūpiNo”, and many more. In essence, Kanniks has done a superb job of both introducing the fundamentals of Vedānta and subsequently illuminating Dīkshitar’s contributions in this divine and sublime space.

Kanniks’ scholarly completeness is evident in his acknowledgment of the contributions of other researchers. He uses the opportunity to encourage more scientific research on Dīkshitar’s compositions, as was published by another researcher showing statistically significant improvement in overall development, cognitive skills, communication skills and social-emotional development in children exposed to the background Nottusvara music intervention, compared to the historical control group. It is no surprise, then, that the author appears to have alluded to a potential “Baby Dīkshitar” effect akin to the widely known “Baby Mozart” effect.

While expert readers may occasionally wish for additional musical notation, Kanniks strikes an admirable balance by providing ample narrative breadth and depth for every technical subject he tackles. He beautifully interweaves raga frameworks, Sanskrit meters, temple architecture, soulful stories, pilgrimage geography (dig vijaya), colonial musical encounters, tantra and mysticism, six streams of worship (śaṅmatā), and integration of pan-Indian cultural currents across Dīkshitar’s era and our own.

It invites lovers of India’s traditional music, its spiritual heritage, and its cultural history to embark on a profound journey. Ultimately, this book is not merely a biographical or musicological study; it ventures into the very heart of Dīkshitar’s artistic, spiritual, and cultural legacy for centuries and millennia to come. It also stands as a testament to the living tradition of Indian classical music in the diaspora, embodied in Kanniks’ own vision of community, choral expression and cross-cultural artistry.

Taken together, Dr Kanniks Kannikeswaran masterfully situates Dīkshitar as not merely a composer but as a traveller, a philosopher, a devotee, and a synthesiser of traditions.

The author’s own life and work bear a striking imprint of Shri Muthusvāmi Dīkshitar’s model of substantial contributions, illuminating a profound musical and personal lineage. Importantly, both Kanniks and this book are invaluable global treasures that deserve to be celebrated, disseminated, and deeply studied for generations. This volume is a must-read for anyone connected to sound in any shape or form—essentially everyone!

Viswanathan Rajagopalan is a PhD, FCVS. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177071104548613514.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177069883355864652.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177070512991253005.webp)