About nine decades ago, on January 15, 1934, the earth shook violently along the India-Nepal border, turning an ordinary winter afternoon into one of the subcontinent’s darkest days. At around 2.13 pm, as people sat down for lunch, children played outdoors and markets bustled, a massive earthquake ripped through the Himalayan region, flattening towns and permanently altering the landscape.

What followed was not a routine tremor but a catastrophic Himalayan quake that struck with a magnitude estimated between 8.0-8.3 on the Richter scale. The epicentre was eventually confirmed to be in eastern Nepal, roughly 9-10 kilometres south of Mount Everest, though early reports had mistakenly placed it in the plains of Bihar. The quake occurred along the Main

Himalayan Thrust, where the Indian tectonic plate collides with the Eurasian plate, releasing centuries of accumulated stress in a matter of seconds.

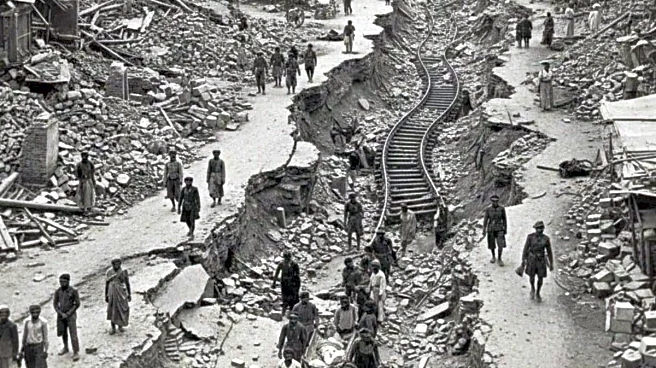

The shaking was so intense that buildings swayed in Kolkata, nearly 650 kilometres away. Tremors were felt across a vast region, from Lhasa in Tibet to Punjab. Entire cities crumbled. In India, places such as Munger, Muzaffarpur and Darbhanga almost wiped out, while in Nepal, large parts of the Kathmandu Valley, including Bhaktapur and Birgunj, lay in ruins. Ancient temples collapsed, roads split open, bridges were swept away and railway tracks twisted beyond repair.

The human toll was staggering, though never precisely recorded. British-era reports put the death toll in Bihar alone at 7,253, while losses in Nepal were believed to be even higher. Most historians and seismologists today estimate that between 10,700 and 12,000 people died, though some local accounts place the figure at over 15,700, and even above 20,000. Many of the injured succumbed days later, and fatalities from remote areas of Nepal were reported much later, adding to the uncertainty.

Beyond the immediate destruction, the earthquake reshaped the region’s geography. Major rivers along the India-Nepal border, including the Kosi, Gandak and Bagmati, altered their courses after massive landslides, ground subsidence and soil liquefaction. In Bihar, a 300-kilometre-long slump belt formed as land sank by several metres. Villages disappeared, farmlands were damaged and, in some places, even the international border shifted. These changes proved permanent, with altered river paths and flood patterns still evident today.

Relief and rescue efforts unfolded under severe constraints. In British India, Bihar Relief Commissioner WB Brett coordinated operations, supported by local leaders such as Shrikrishna Singh, Anugrah Narayan Singh and Magfur Ahmad Ajazi. Mahatma Gandhi visited the affected areas to assess the situation. In Nepal, Maharaja Juddha Shamsher mobilised the army to clear debris, rescue survivors and establish relief camps. Soldiers, volunteers and ordinary citizens worked tirelessly, distributing food, clothing and medicines. Yet cold weather, poor communication and limited infrastructure meant that help often arrived too late.

Looking back, the 1934 earthquake stands as a grim warning. Today, the population of the region is estimated to be 10 to 20 times higher. Cities like Patna, Muzaffarpur and Kathmandu are far more densely populated, with unplanned construction, high-rise buildings and sprawling slums increasing vulnerability. The 2015 Gorkha earthquake in Nepal, with a magnitude of 7.8, claimed around 9,000 lives. Experts warn that if a quake of the scale seen in 1934 were to strike now, the death toll could run into the millions.

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177100504592948655.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177101053501199609.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177101003680064644.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177100753350744656.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-17710070301901476.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177100572282276854.webp)