Indian Test cricket hit a new low on Wednesday as South Africa sealed a historic 2-0 series win, finishing with a commanding 408-run victory in the second Test at Guwahati. What many expected to be a comfortable

outing for India — especially after the 2-0 win against the West Indies — turned into a one-sided contest, but not in favour of the hosts.

With this result, South Africa not only inflicted India’s biggest-ever home Test defeat but also became the only team to whitewash India twice on Indian soil — first in 2000 under

Hansie Cronje, and now, 25 years later, under Temba Bavuma.Lowest Point In Tests

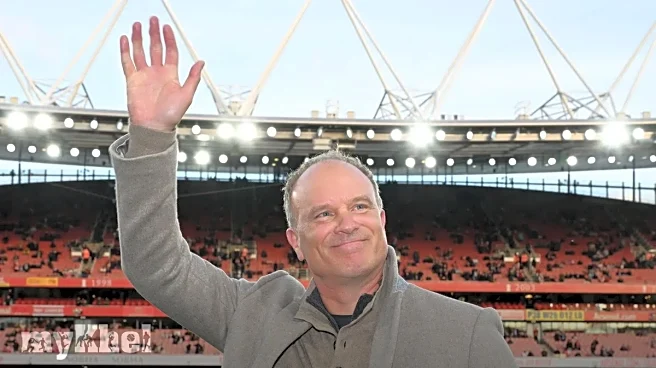

The South African coach Shukri Conrad, on the penultimate day of the series, aptly described India’s capitulation as a Test team. His team wanted to make India “grovel”, Conrad said with a smirk, when asked why South Africa chose to bat on even after their lead went past the record chase of 418 on Tuesday. The Proteas had an unassailable 1-0 lead in the series, with a 30-run win in the first Test at Kolkata.

The comment drew mixed reactions, with some criticising Conrad for using the term grovel — a word that carries deep historical weight in cricket. In 1976, former England captain Tony Greig — a white South African — infamously said he wanted to make the West Indies “grovel”, a comment widely condemned as racially charged and laced with colonial undertones.

However, Conrad, a mixed-race South African, appeared to be channeling his team’s sheer cricketing superiority rather than invoking any historical echoes. But the symbolism stung because the cricket matched the word: Indian team was made to crawl. This series ranks among the lowest points in India’s 93-year Test history.

Year Of Uncertainty

India’s decline began a year ago when New Zealand toured India and stunned the hosts with a 3-0 clean sweep — the first time India had ever been whitewashed at home in a Test series. That setback was followed by a 1-3 loss in Australia, which cost India a place in the World Test Championship final.

A 2-2 draw in England provided only temporary relief, driven largely by individual brilliance from captain Shubman Gill and Mohammed Siraj, and assisted by England’s erratic Bazball experiments. India’s 2-0 win over the West Indies last month offered a momentary lift, but it came against a side ranked eighth among 12 Test-playing nations.

What Went Wrong?

Test cricket has long been the ultimate yardstick of ability — the format where good players become great and greats become legends. Yet, in recent times, the Indian team management and selectors seem to be moving in a direction that challenges this very belief. Decisions around transition and team selection have appeared hurried, reactive and lacking long-term clarity.

Over the past year, senior players, who could have guided a smoother handover, were eased out well before a natural transition could take place. Rohit Sharma, Virat Kohli and R Ashwin exited with their spots handed to players who collectively have only a handful of Test seasons behind them.

Squads have changed constantly. India have rarely fielded the same XI in consecutive Tests.

The batting order has resembled a musical-chairs competition more than a strategy — openers become middle-order batters, middle-order batters are asked to “float”, tailenders have turned batters and all-rounders are picked to either bat or ball but not do both. India’s batting lineup has been so “fluid” that fans have struggled to remember who’s injured, who’s rested and who’s simply out of favour.

The bowling unit has been equally unsettled. The decline in the quality of spinners selected has forced Indian pitches — once a major home advantage — to be prepared in ways that inadvertently favour visiting bowlers. Surfaces that should test skill and temperament have instead become unpredictable and poorly suited to India’s strengths.

Indian pitches deserve a chapter of their own. Instead of producing good cricketing wickets — the kind that test skill, temperament and talent — we now have strips that behave erratic. Some turn square from ball one, others remain flat deep into the match, most doing more favours for the visitors than the hosts. Instead of producing cricketing wickets, India has produced surfaces that only magnify the team’s weaknesses.

Another major contributor to the current imbalance has been the unnecessary fascination with all-rounders who are, in reality, bits-and-pieces T20 players rather than genuine Test-quality multi-dimensional cricketers. These are not the calibre of Jacques Kallis, Ben Stokes or even peak Ravindra Jadeja — players who could walk into a Test side as specialists in either skill. Instead, India have repeatedly fielded cricketers who are neither dependable top-order batters nor consistently threatening bowlers, leading to a diluted playing XI.

Test cricket demands specialists with the temperament and skill to either bat long or bowl tirelessly, and an all-rounder should only be picked when he truly merits the spot on both fronts. The current approach has added confusion, reduced accountability, and weakened the core structure of the team.

Add to all this the opaque communication, muddled long-term planning, and the constant compulsion to experiment, and the picture becomes clearer. India’s recent run is not a blip — it is the result of systemic uncertainty.

Coach Gautam Gambhir and chief selector Ajit Agarkar, who have overseen this period of drastic churn, must now provide clear answers. The Indian team hasn’t just lost Test matches — it has lost its rhythm, its clarity, and occasionally, its common sense.

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177075852740281148.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177075603605816191.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-17707550296985796.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177075157301840277.webp)