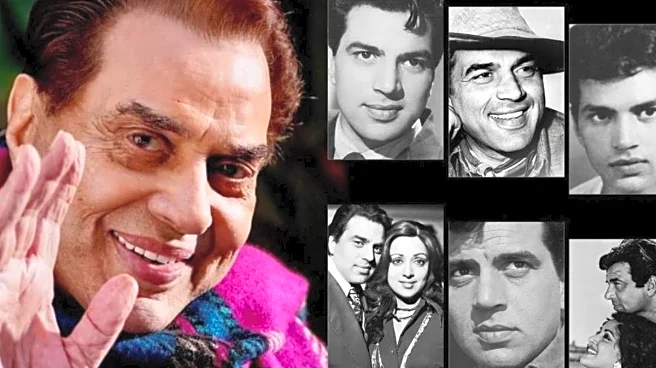

The lights have dimmed on the man whose presence once felt effortless. Dharmendra — Hindi cinema’s original “He-Man,” strength tempered with sensitivity — passed away on 24 November 2025, aged 89. With him goes not just an icon, but a particular idea of heroism: unforced, decent, inwardly anchored.

Born Dharam Singh Deol in Punjab, he was already married to Prakash Kaur when he won a talent contest and came to Bombay chasing a dream — to become a star like his idol, Dilip Kumar. If Dilip gave tragedy its refinement, Dharmendra gave physicality its grace. Over 300 films — Sholay to Chupke Chupke, Anupama to Phool Aur Patthar — he brought vulnerability to valour, making masculinity feel human. Built on farm work, restraint and discipline, he resisted

the flamboyance the industry often demands. The physique was legendary, but what endured was the emotional musculature: the ability to remain uncomplicatedly good.

Shaped by the Bengali Sensibility

Bollywood didn’t invent Dharmendra’s heroism; it witnessed and then structured itself around it.

His debut, Dil Bhi Tera Hum Bhi Tere (1960), arrived without flourish. It was Shola Aur Shabnam the following year that hinted at a new screen presence — sculpted but not aloof. By Phool Aur Patthar (1966), the template had crystallised: moral courage matched with physical certainty. In Anupama, Bandini, and Satyakam, he became proof that strength could carry conscience.

The most defining hand in this transformation came not from mainstream action cinema, but from Bengali filmmakers who saw beyond his exterior. Bimal Roy cast him in Bandini (1963) after a recommendation — not for his face or build, but for instinct. Roy’s precision and aversion to excess shaped Dharmendra’s early sensibility. He would often recall the experience not as an opportunity, but as orientation.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee deepened that trajectory. Their first film together, Anupama (1966), revealed an actor whose authority lay in understatement. Satyakam (1969) — often cited as Mukherjee’s most personal work — offered Dharmendra one of his finest roles, that of a man uncompromised by circumstance. The performance was unadorned, and that was its power.

They continued through Majhli Didi, Guddi, and Chupke Chupke, films where he shifted between resilience and levity without disconnecting from truth. Bengali filmmakers valued emotional rigour and moral centre — Dharmendra, perhaps unexpectedly, carried both.

He once remarked that he “felt like a Bengali.” What he meant was that he recognised in their cinema a rhythm he could naturally inhabit — measured, direct, without affectation.

That early training allowed him to move between genres without altering himself. The industry celebrated his build; the filmmakers who shaped him valued his balance.

Dharmendra’s image as Hindi cinema’s indomitable strongman truly crystallised with Phool Aur Patthar (1966). Until then, he had been seen mostly as a serious actor from socially conscious films. But OP Ralhan’s unexpected blockbuster redefined his career and reshaped the idea of screen masculinity. As Shaaka — a hardened man with a conscience — Dharmendra brought a striking balance of power and emotional restraint. His physical presence drew attention, but it was the compassion beneath that surprised audiences.

In one of the film’s most quietly unforgettable scenes, the male body became a symbol of both damage and dignity. Meena Kumari’s widow lies trembling in silence. Dharmendra enters, pauses, and instead of approaching with threat or desire — as cinema often once coded such moments — he removes his shirt and places it gently over her. No words, no bravado. Just protection. In that simple gesture, strength transformed into care.

That moment triggered his “He-Man” mythology — not because he bared his chest, but because he used it to shield, not dominate. Audiences saw toughness shaped by empathy. Critics recognised a masculinity that could be strong without aggression, and the performance earned him his first Filmfare nomination.

After Phool Aur Patthar, roles began to follow this persona: the rugged hero driven by principle. Even when some films were later dismissed as overly commercial, his appeal endured. He didn’t reject the image — he refined it, proving with Satyakam that he was not just a star of muscle, but of conviction.

Outside the Orbit of Stardom

When Rajesh Khanna’s wave of superstardom hit in the late 1960s, the industry recalibrated itself around hysteria and worship. Dharmendra, at the height of his career, did not. He had already transitioned into stardom without theatrics, and without requiring the phenomenon that others needed to ascend. “Number one, number two — I never bothered,” he said later. It rang true not because he was unaffected, but because he never positioned himself inside that framework.

In Mera Gaon Mera Desh (1971), he pioneered the Hindi film “curry western” before Sholay was even conceived — rugged, charismatic, but still human. Loafer (1973) extended that template, blending action with irreverence, allowing the hero to be flawed without moral collapse. He carried the film through persona rather than myth, and audiences responded not with frenzy but with familiarity.

Where Khanna represented infatuation and Amitabh later embodied rebellion, Dharmendra occupied a quieter space — trusted rather than idolised. His presence didn’t need cinematic redesign; instead, narratives moulded themselves around the equilibrium he brought. He didn’t chase reinvention because he was built on continuity.

And when Amitabh emerged, Dharmendra didn’t contest the shift. He worked alongside him in Sholay, allowing the younger actor’s brooding intensity to coexist with his own ease. Bachchan would often refer to him as an elder brother — not by hierarchy, but by instinct.

Dharmendra didn’t survive superstardom. He simply wasn’t formed by it.

The Lightness Within the Strongman

By the 1970s, when most actors doubled down on muscle and myth, Dharmendra did something subtle: he loosened his grip.

In Chupke Chupke (1975), as Professor Parimal Tripathi masquerading as a driver, he didn’t play comedy — he discovered it. This was the action hero weaponising grammar, modestly donning a driver’s cap and letting the laughter occur quietly around him. Instead of lifting cars, he lifted timing. The humour arrives like a well-measured pause: so confident that effort seems optional.

That same year in Sholay, Veeru moved like someone whose laughter always beat his logic by a half-step. He flirted with Basanti at horseback speed and staged a drunken protest atop a water tank, as though intoxication were explanation enough. Then, when Jai dies, the same kinetic energy compresses into focus — no theatrical pivot, just a tightening of purpose. The comic instinct and the vengeful one spring from the same reservoir.

His home production Pratiggya (1975) reinforced the point — part bravado, part self-parody of bravado — proof that he could mock his own shadow and still fill theatres in the same year as Sholay.

Then came Dillagi (1978). Directed by Basu Chatterjee and adapted from a story by Bimal Kar, it entrusted him with Swarn Kamal, a newly appointed Sanskrit professor in a women’s college. His adversary-turned-romantic target: Phoolrenu (Hema Malini), the chemistry lecturer-warden dubbed “CO₂” by students for her icy resolve.

His wooing is persistent, not flamboyant — a day-one crush, a Holi intrusion at the girls’ college, Sanskrit murmurs in the corridor, uninvited summer visits to her hometown. She runs on rules and hostel registers; he runs on instinct. She asks him to apply through a matrimonial ad; he shows up instead. She bolts her heart behind protocol; he keeps knocking.

The Ease of Their Togetherness

When Dharmendra and Hema Malini began appearing together in the early 1970s, what drew audiences in was not storm or spectacle, but ease. Their screen chemistry thrived on charm, playfulness and timing — a romance propelled not by intensity but by enjoyment. He brought the sparkle, she the balance; together, they made affection look unforced.

In films like Raja Jani, Jugnu and Naya Zamana, the dynamic was established — he pursued with amused persistence, she resisted with calm intelligence. Even in Sholay (1975), amid guns and legend, their romance played like a private wind — lighter than the rest of the film, a necessary exhale. Dillagi (1978) continued this tone of softly comic pursuit, a tenderness framed in everyday gestures.

Only later did their pairing deepen into quieter emotional terrain, most notably in Gulzar’s Kinara (1977). Here, the playfulness gave way to introspection. He carried regret with restraint; she held grief without display. For once, they were no longer teasing each other — they were listening.

Off screen, what began in on-screen ease matured into companionship. Dharmendra, already married, chose to marry Hema in 1980. The decision drew commentary, but their relationship did not seek validation. Unlike the films that announced love with song, their union arrived quietly and stayed.

The Smouldering Rebel — Post-Eighties Dharmendra

By the mid-1980s, when many stars leaned into self-mythology, Dharmendra turned inward. Ghulami (1985) didn’t revive the baagi narrative — it dismantled its legend. In the scorched terrain of Rajasthan, JP Dutta reframed rebellion not as a dacoit’s swagger but as a peasant’s inevitability. Here, oppression wasn’t worn in chains but printed on land deeds, caste contracts and unpaid loans.

Dharmendra plays a Jat farmer born into resistance. He doesn’t roar; he smoulders. The heroism is weary, divested of ornament — a battle waged without illusion of victory. Strength becomes endurance. In Ghulami, the former He-Man doesn’t break walls — he recognises they were always there. And still walks toward them.

Around this time, the arc shifted off-screen too. His elder son, Sunny Deol, stepped into cinema, soon to channel a younger version of that defiance in films like Arjun, Dacait, Ghayal and Damini. A decade later, Bobby Deol arrived with Barsaat, Gupt, Soldier — carving a different trajectory but born of the same instinct for cinematic presence. The baton had passed; the blowtorch had dimmed.

Dharmendra, meanwhile, moved from force to resonance. He had played the fighter. After Ghulami (1985), Dharmendra didn’t step away — he simply stopped needing to lead. The films kept coming, but without urgency. The industry shifted lanes; he didn’t sprint to keep up. The man who once entered frames like impact began to move through them like memory. Not absence, but an easing.

That instinct echoed off-screen. In 2004, he contested from Bikaner on a BJP ticket and entered Parliament. The win was emphatic; the tenure, deliberately quiet. He campaigned with belief but didn’t perform politics. Attendance was sparse, speeches rare — no attempt to command the space. After one term, he left without ceremony, later admitting an actor should stay an actor. It wasn’t failure; it was the same refusal to overstate.

So when he returned to the cinematic centre in Johnny Gaddar (2007), Life in a… Metro, Apne, even the looseness of Yamla Pagla Deewana, it wasn’t as Dharmendra the myth. It was Dharmendra the man — wry, unguarded, quietly assured. The presence still held weight, but without pressing it. You smiled because he seemed in on the moment.

What resurfaced wasn’t the strongman. It was someone strong enough to stop acting strong. That — more than the muscle, more than the myth — is what endures.

The Last Act — With Light Still in the Eyes

In his final years, Dharmendra spent much of his time at his farmhouse — a little apart from his families, but never disengaged. He lived quietly, though not silently. Social media became his informal drawing room, where he would greet the morning with unstyled honesty, talking to the camera among trees, sometimes playful, sometimes reflective, always recognisably himself.

It felt, in a way, like the long echo of a moment from the very beginning of his career: when he sang Kaifi Azmi’s “Jaane kya dhoondti rehti hain ye aankhen mujh mein” to Tarla Mehta in Shola Aur Shabnam (1961). The young actor, observed by eyes unsure of what they sought, already carried a secret inner world — that of a closet poet speaking to himself in shayari. Across the years, that creative undercurrent deepened through his admiration of Dilip Kumar’s literary gravitas and his emotionally charged rapport with Meena Kumari, both connoisseurs of language and silences. They showed him how one could be a mass favourite while still holding on to nuance, how a line could be delivered like a verse. From them, he learned to speak less like a star and more like someone listening between words.

Ironically, the man whose screen persona leaned on physicality spent much of his real life shaped — even wounded — by delicacy: by couplets, pauses, the nazakatof Urdu. The He-Man remained, but the poet steadily stepped forward.

He often spoke with candid humour about his past — including his fondness for drink and the night he reportedly kept Hrishikesh Mukherjee awake insisting the role in Anand should have been his. There was no bitterness in the memory, only the laughter of a man who never quite detached from passion.

He remembered lost colleagues with tenderness, reconnected with a few still living, not as an icon visiting history but as an actor still stirred by it.

And always, he recited. Verses he wrote himself — sometimes casually, sometimes with startling clarity — trusting words to carry what physical strength no longer needed to. What endured was his zest, his humour, his refusal to retreat from feeling.

He didn’t fade.

He adjusted — gently, still lit from within.

Shortly before the end, he shared these lines he had written himself:

“Sab kuch pa kar bhi hasil-e-zindagi kuch bhi nahin,

Kambakht jaan kyun jaati hai, jaate hue.”

Rajeev Srivastava is a filmmaker, writer, and photographer with a deep engagement in Indian cinema. He has taught film, curated two international film festivals at Siri Fort, and exhibited his photography at Bikaner House, New Delhi, in April 2025. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177043890097897507.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177043885979790635.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177044253007719444.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177044253969765152.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177044133305295404.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-17704400555374587.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177044003399948153.webp)