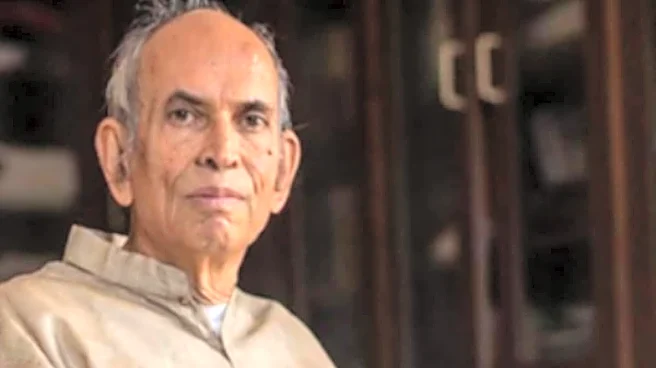

A giant in Indian ecology, Madhav Gadgil, passed away on Wednesday night, January 7, in Pune, Maharashtra, following a brief illness. He was 83. Gadgil was celebrated for his lifetime of work in conserving

the Western Ghats and for promoting a community-centered approach to environmental protection.

“I am very sorry to share the sad news that my father, Madhav Gadgil, passed away late last night in Pune after a brief illness,” said his son Siddhartha Gadgil in a statement.

From an early age, Madhav was drawn to the forests and hills of the Western Ghats. Born in 1942, he was inspired by the region’s rich biodiversity and cultural heritage which shaped his lifelong commitment to ecological study.

According to Penguin, which published his autobiography A Walk Up The Hill: Living With People And Nature in 2023, Gadgil decided while still in high school to pursue a career that combined field ecology with anthropology. His academic journey took him from Pune and Mumbai to Harvard University where he completed a doctoral thesis in mathematical ecology.

Champion Of The Western Ghats And Biodiversity

Throughout his career, Madhav made major contributions to environmental science and policy. He was a professor at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, and founded the Centre for Ecological Sciences which became a leading hub for research in India.

He chaired the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel, widely known as the Gadgil Commission, which proposed designating large parts of the Western Ghats as Ecologically Sensitive Areas. He also served on the Scientific Advisory Council to the Prime Minister and chaired the Science & Technology Advisory Panel of the Global Environment Facility.

Science Meets Action

Madha helped establish India’s first biosphere reserve, the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, in 1986. This linked conservation science with government action.

He also helped shape the Biological Diversity Act, 2002, and championed People’s Biodiversity Registers which involve local communities in documenting and protecting biodiversity. Madhav highlighted that people are an important part of ecosystems and worked on studying animal behaviour and ecological patterns in India.

Honours And Global Recognition

For his work, Madhav has received Padma Shri in 1981 and Padma Bhushan in 2006. Internationally, he was awarded the Volvo Environment Prize and the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement.

In 2024, United Nations Environment Programme named him a “Champion of the Earth” in the Lifetime Achievement category for his work on the Western Ghats.

Roots In Maharashtra

Madhav’s connection to Maharashtra remained central to his life and work. He wrote extensively in Marathi, including books like Nisarganiyojan Lokasahabhagane and over 40 articles, along with a monthly column in Sakal newspaper focused on ecology.

He studied sacred groves (devrais) with V.D. Vartak, a renowned botanist and philanthrophist, across the state and documented how local communities protected these forests. Not only this, his research on Koyna Dam on Krishna River also influenced people to lean towards sustainable methods.

Aarey To Sanjay Gandhi National Park: Madhav Gadgil’s Efforts In Mumbai

His work also benefited Mumbai as his research influenced the protection of Sanjay Gandhi National Park and Aarey Milk Colony which act as critical buffers against flooding, pollution and heat.

Native afforestation and community-led restoration were two main factors led by Madhav that helped Mumbai maintain green cover amid rapid urban growth.

His Push To Save Western Ghats In Kerala

Gadgil’s work strongly shaped conversations around ecology in Kerala, especially through the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel that he headed. The panel suggested that large parts of the Western Ghats in the state needed strict protection to prevent damage caused by mining, quarrying and unchecked construction.

At the time, many of these suggestions were pushed aside, but Gadgil continued to warn that ignoring ecological limits would come at a cost. Over the years, he often linked Kerala’s recurring floods and landslides to activities like hill cutting and illegal quarrying that had gone on despite clear environmental warnings.

The WGEEP report also proposed zoning large stretches of the Ghats as ecologically sensitive, with restrictions on destructive activities to protect forests, water sources and biodiversity-rich areas.

Even after later reviews and diluted versions of the report, including the Kasturirangan panel, Gadgil’s ideas continued to influence environmental debates in the state. He earned widespread respect in Kerala where he came to be known as the state’s “people’s scientist.”

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177102753183257032.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-17710264327998831.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177102646607765106.webp)