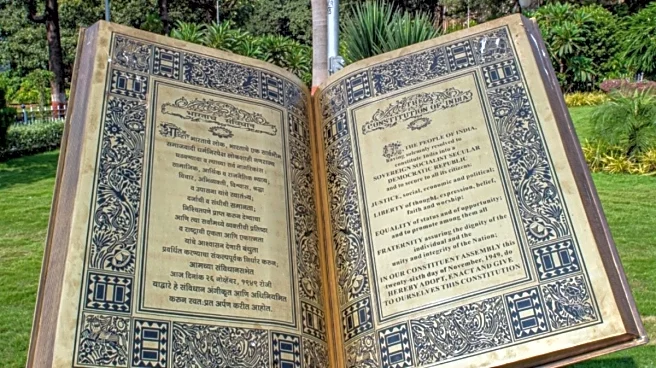

The Indian Constitution rests on a foundational insight: national unity does not require cultural uniformity. The framers imagined a republic in which India’s many languages, faiths, and traditions could flourish within a shared civic and economic framework. Minority rights were crafted as guarantees of confidence — designed to assure communities that cultural distinctiveness and national belonging could advance together. Yet, over time, the public conversation on minorities often narrowed. Cultural protection came to be treated as an end in itself, while education, skills, and livelihoods were addressed through fragmented welfare measures. This separation produced unintended consequences. Cultural traditions risked becoming static, while development

interventions sometimes created dependency rather than agency. A more durable approach required recognising that cultural vitality and material progress reinforce one another. In recent years, the Modi government has attempted to address this imbalance. The current policy orientation seeks to preserve minority heritage while expanding access to modern education, formal credit, and economic opportunity—positioning minorities as equal stakeholders in India’s growth rather than passive recipients of state support. The principle underlying this approach is constitutionally consistent: cultural confidence strengthens when communities possess the tools to succeed in a modern economy. The Constitution itself offers clear guidance. Articles 29 and 30 protect the right of minorities to conserve culture and to establish and administer educational institutions. Judicial interpretation over decades has clarified that these provisions are meant to ensure security and integration, not isolation. This balance was reaffirmed in the Supreme Court’s 2024 judgment on the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, which upheld the state’s authority to regulate educational standards while preserving the minority character of institutions. The ruling underscored a central idea: autonomy and accountability can coexist in ways that protect both heritage and students’ future prospects. Education remains the most effective bridge between identity and mobility. Empirical evidence consistently shows that secondary education is a critical threshold for improving labour force participation, health outcomes, and intergenerational mobility. Targeted interventions such as the Begum Hazrat Mahal National Scholarship address precisely this point, supporting minority girls at the secondary level, where dropout rates rise sharply due to financial and social pressures. Since its inception, the scheme has benefited over six lakh minority girls, helping them remain in school during a decisive phase of their education. The effects extend beyond classrooms—shaping workforce participation, household stability, and long-term aspiration. Equally important has been the effort to modernise traditional educational institutions through mainstream linkages rather than coercive restructuring. Programmes that introduce modern subjects, digital literacy, and recognised certification pathways into madrassa education have expanded student choice. Linkages with the National Institute of Open Schooling allow learners to access Class 8, 10, and 12 certification, enabling entry into higher education and skilled employment. This approach strengthens social mobility while respecting institutional identity, ensuring that cultural preservation does not come at the cost of economic exclusion. Economic participation further anchors this model. Universal credit programmes such as the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana have enabled minority entrepreneurs to enter the formal financial system at scale. Government data shows that minorities account for roughly 11 per cent of Mudra loan beneficiaries, spanning micro-enterprises in trade, services, and manufacturing. For many first-time borrowers, access to collateral-free institutional credit replaces reliance on informal lenders, formalises economic activity, and builds a credit history. This form of economic citizenship reinforces dignity, positioning beneficiaries as contributors to growth rather than recipients of charity. Cultural conservation, too, has been reimagined as an economic and social asset. Platforms such as Hunar Haat connect artisans and culinary experts from minority communities directly with national markets, transforming inherited skills into viable livelihoods. Official figures indicate that over 5 lakh artisans and associated workers have generated employment opportunities through these platforms. When heritage produces income and recognition, it attracts younger generations and sustains living traditions. Complementary initiatives under Hamari Dharohar invest in documenting and showcasing minority cultures, affirming their place within India’s civilisational narrative. Beyond targeted programmes, the emphasis on welfare “saturation” has had significant implications for minority communities. Universal schemes in housing, sanitation, water, and electricity—implemented with a focus on high-deficit districts—have reduced everyday vulnerabilities. According to the National Multidimensional Poverty Index, India lifted 24.82 crore people out of multidimensional poverty between 2005–06 and 2019–21, with some of the steepest declines observed in states with substantial minority populations. These gains reflect the impact of delivering basic services at scale, without segregating beneficiaries by identity. Labour market trends point in a similar direction. Periodic Labour Force Survey data shows a notable rise in female labour force participation across communities, including a sharp increase among Muslim women—from 15 per cent in 2021–22 to over 21 per cent in 2023–24. While gaps remain, the trajectory suggests that education, skilling, and economic necessity are together reshaping participation patterns. The strength of this policy approach lies in its refusal to frame heritage and progress as competing claims. Cultural preservation gains meaning when communities are equipped to navigate a changing world. Economic and educational advancement gains legitimacy when it respects identity and tradition. By grounding minority policy in constitutional principles and measurable development outcomes, the current model seeks to move beyond symbolic protection towards durable empowerment. India’s unity depends on this synthesis. A society in which minorities can prosper without relinquishing their identities strengthens both democracy and development. Protecting heritage while ensuring progress affirms a simple truth: diversity is not a constraint on national growth. It is one of its enduring foundations.

Akshara Bharat is a Senior Communications Associate at IFMR. Her work spans geopolitics, national policy analysis, and sociopolitical issues. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177100504592948655.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177101053501199609.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177101003680064644.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177100753350744656.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-17710070301901476.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177100572282276854.webp)