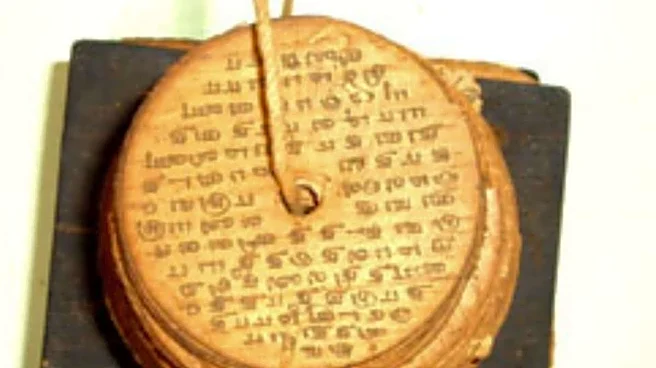

In his recent Independence Day Speech, Prime Minister Narendra Modi mentioned about his government’s “Gyan Bharatam Mission” that aims to preserve, document, digitise and disseminate India’s rich heritage

of antique hand-written manuscripts. Gyan Bharatam Mission is a restructured form of the National Mission for Manuscripts (estd. 2003).

The Minister of Culture and Tourism viz. Gajendra Singh Shekhawat had informed the Lok Sabha (vide Unstarred Question No. 3905) on March 24, 2025 that under the National Mission for Manuscripts, 5.2 million manuscripts have been documented across India, approximately 3.5 lakh manuscripts containing over 3.5 crore folios had already been digitized. Over 1,35,000 manuscripts have been uploaded on the Mission’s web portal namami.gov.in out of which 76,000 manuscripts were available for free. An allocation of Rs. 482.85 crores has been made for the period of 2024-31.

The National Manuscript Mission (NMM), which is administered by Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts (IGNCA) has grown over the last two decades since its inception by the Vajpayee government. The government has identified 15 major manuscript repositories holding between 12,000 manuscripts (Oriental Research Library, J&K) and 250,000 manuscripts (Acharya Shri Kailashsuri Jnanmandir, Koba, Gujarat) with which it works closely. The minor manuscript repositories are 3851 in number, which include foreign institutions like Bibliotheque Nationale de France (Paris) and India Office Library collection now incorporated in British Library, London etc. The Mission publishes a bi-annual journal viz. Kriti Rakshana, though its periodicity has been somewhat irregular of late.

While launching the National Mission for Manuscripts on February 7, 2003 in New Delhi the then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee had provided an estimate of 35 lakh manuscripts in the country, most of these being in Sanskrit. It was naturally an underestimation, as 5.2 million (or 52 lakh) manuscripts have already been documented. He had hoped the Mission would bring to light several “Harappas, Mohenjo-daros and Dwarkas in the future in the field of manuscripts”.

Two decades later we are yet to witness the rediscovery of any “Harappa, Mohenjo-daro or Dwarka” through the manuscripts. No groundbreaking discoveries known to the public have been made. Is it because the time span allowed is too short, during which we are able to digitize only 7 (seven) percent of the estimated number of manuscripts? In the same period thousands of palm leaf manuscripts, mostly in private hands, might have also perished from sheer neglect and ravages of nature. No public awareness campaign was launched for their collection. That is, however, not the real reason.

Harappa and Mohenjadaro were discovered because there were men like Rakhaldas Banerji (1885-1930) and John Marshall (1876-1958) who could see the ruins as part of India’s history as poet laureate Kalidas could describe a mass of wood kept in front of him as lifeless tree (“Nirasa tarubara purata bhage”).

II

Preserving manuscripts and digitising them is the preliminary step. However, they could not broaden our mental horizons, unless they are made a part of the knowledge ecosystem. This requires proper publication of critical editions/translations of the works. Such ventures are laborious and call for scholarly intervention and supervision. Though the government says that editing, translating and publishing rare and unpublished manuscripts to promote scholarly research is part of the Gyan Bharatam Mission, no particulars or actual figures are provided in this regard.

Critical editions are important. For example, when the play Mudrârâkshasa by Vis’âkhadatta was published by Tukaram Javaji Dadaji’s “Nirnay Sagar” Press (Bombay) we are told that nine different copies of manuscripts sourced from different locations had been consulted and compared to prepare the printed text. It was edited with critical and explanatory notes by illustrious Kashinath Trimbak Telang (1850-1893), the Indologist and Judge of Bombay High Court.

Discoveries of Sanskrit manuscripts followed by the publication of their critical edition/translation have played major role in redefining ancient Indian history. H.H. Wilson, an Orientalist associated with Asiatic Society was the first to partially translate Kalhana’s Rajtarangini in 1825. In the 1850s, the first American Indologist, Professor Fitz-Edward Hall, discovered Bana’s Harsha Charit, which was subsequently published from Jammu & Kashmir in 1879, and Bombay in 1892, before E.B. Cowell and F.W. Thomas published its translation with the sponsorship of Oriental Translation Fund of Britain.

Bilhana’s Vikramankadevacharita, a life of 11th century Chalukya monarch Vikramaditya-Tribhuna Malla of Kalyan, was spotted by German Indologist Georg Bühler in a Jain Bhandar (manuscript depository) in Jaisalmer. Bühler edited and published it under the Bombay Sanskrit Series (No. XIV) in 1875.

The French scholar Eugène Burnouf (1801-52) in his 647-page long Introduction à l’historie du Buddhism indien (1844) was the first to provide accurate information and insight into Buddhist religion and philosophy from Sanskrit sources. He did it on the dint of the Sanskrit manuscripts sent to him in Paris by Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-94), who was posted as the representative of East India Company in Kathmandu. The bulk of these manuscripts must have carried to Nepal by Indian Buddhist Pandits on their heads, while they escaped to the Himalayan kingdom in the wake of the Turk invasions at the end of the 12th century. The great centres of Buddhism like Nalanda, Jagaddal, Vikramshila and Odantipur had been laid to waste by Turk invasions. Hodgson had evinced an interest in the Buddhist legacy of Nepal since 1821 when he was first posted in Nepal as Assistant Resident. He sent the acquired manuscripts in multiple bundles to various oriental institutions of the world including. R.C. Dutt, I.C.S. informs 85 bundles were sent to Asiatic Society of Bengal, 85 to Royal Asiatic Society London, 30 to India Office Library in London, 7 to Bodleian Library in Oxford and 174 to Societe Asiatique in Paris to Monsieur Burnouf personally (A History of Civilization in Ancient India, 1891, P.344)

The fortuitous acquiring of a manuscript by R. Shama Sastry, librarian of Mysore Government Oriental Library, led to the discovery of Kautilya’s Arthaśástra. The manuscript had been deposited to the Library by a Pandit of Tanjore district. If Shama Sastry were only a graduate in library science, the best he could have done was to catalogue the manuscript. Shama Sastry, a Sanskrit expert, perused the text, to realize the value of treasure he was holding in his hand. Initially he wrote a few essays on it for the journal Indian Antiquary in 1905. Subsequently, he published the complete translation of the text, with sponsorship from the Mysore Durbar in 1909. The rest was history. It was re-published in 1915 with an introduction by Dr. J.F. Fleet, ICS (Retd) and Indologist.

The rest was history. The appearance of Kautilya Arthaśástra revolutionized the world’s understanding of Indian ancient history, and advancement achieved by the ancient Hindus in political science. In 1960, the University of Bombay produced a critical edition of Kautilya Arthaśástra by R.P. Kangle. The Arthaśástra could become part of the discourse, because it was not merely preserved but also acted upon. We need scholars like Shama Sastry and Kangle could lead to knowledge accrual from the manuscripts.

III

The existence of a large number of antique manuscripts reveals a rich knowledge culture in the pre-colonial era. However, it simultaneously underscores the effect of the delayed advent of printing press in India. Whereas the movable type printing press was invented in Germany in the 1450s, and introduced in England in 1476 by William Caxton, it was not another three hundred years afterwards that printing press became available in India on a permanent basis. Nathaniel Brassey Halhed’s A Grammar of the Bengal Language (1778), which used both English and Bengali scripts, is believed to be the first book printed in India. The manuscript culture could have ended much sooner as in Europe had printing press become available earlier.

Many manuscripts being in private hands reveal an intricate pattern of knowledge production and dissemination in the pre-print era in India. There was a very limited “public sphere”, and knowledge was transmitted through grooves of Guru-Shishya Parampara. The exclusive possession of a manuscript was considered a matter of pride as much as possession of knowledge. Only worthy pupils were allowed to copy the manuscripts, who in turn allowed their pupils to copy them.

“Instead of producing a succession of freelance thinkers” says Surendranath Dasgupta (1922), “having their own systems to propound and establish, India brought forth pupils who carried traditionary views of particular systems from generation to generation, who explained and expounded them, and defended them against the attacks of other rival schools and which they constantly attacked in order to establish their superiority of the system they adhered” (A History of Indian Philosophy Vol-1, P.63).

IV

Since palm leaves and Himalayan birch are perishable commodities, every manuscript had to be copied and recopied after one or few generations. A manuscript could enjoy greater longevity in dry climatic regions like Rajasthan or Gujarat than damp regions like Bengal or Assam. This recopying process was possibly discontinued by the late nineteenth century, when even children of Sanskrit pundits began to migrate to the modern education system.

However, the repository of manuscripts did not migrate to print format as easily. Sadly, they became unwanted heirlooms within a generation or two in many families. This experience was not confined to Sanskrit alone, whose predominance got eclipsed. Say, manuscripts in Tamil, which is a living and growing language, besides being supported by a strong Dravidian ideology, have fared little better. This was revealed at a three-day national seminar on Palm Leaves and Other Manuscripts in India (January 11-13, 1995) held in Pondicherry University in collaboration with Institute of Asian Studies, Chennai. Even in those pre-internet CD-ROM days the Institute of Asian Studies was involved in preservation of manuscripts through microfilming etc.

Director G. John Samuel informed in the seminar that they had compiled a list of 80,000 Tamil palm leaf manuscripts, out of which 25 percent had ever been put to print, whereas 75 percent were perishing in remote corners of villages or in a number of manuscript repositories. Worse, they were set ablaze during various festivals and thrown into rivers to appease deities during the time of flood. They were sometimes used as fuel to prepare hot waters for horses and human beings.

Proper cataloguing of manuscripts that can act as a ready reckoner for scholars is very important. Raja Rajendralal Mitra (1822-91), the first Indian Secretary of Asiatic Society, devised a method for descriptive catalogue of Sanskrit manuscripts. The tradition of collecting, cataloguing and preserving Sanskrit manuscripts goes back to the British times. Though Asiatic Society (Calcutta), Saraswathi Mahal Library (Tanjore), and the libraries of Maharajas of Jaipur and Nepal were already possessed large collection of Sanskrit manuscripts, it was in 1868 that the administration of Lord Lawrence, Governor General of India, undertook a project for cataloguing and possible collection of Sanskrit manuscripts in private hands at a reasonable price. Orientalists like George Bühler, Rajendralal Mitra, Sridhar R. Bhandarkar, Haraprasad Sastri etc. undertook tours in various parts of India in search of Sanskrit manuscripts. During the 19th century several Oriental institutes were set up in India like at Pune, Mysore, Adyar (Chennai), Baroda etc. There was addition to their numbers in the 20th century.

A proper synergy between critical scholarship and manuscript preservation is required for the Gyan Bharatam Mission to be successful. Are our Sanskrit universities and departments doing enough?

The writer is author of the book ‘The Microphone Men: How Orators Created a Modern India’ (2019) and an independent researcher based in New Delhi. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177090552977584362.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177090530594986069.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177090503458393910.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177090512191059170.webp)

/images/ppid_59c68470-image-177090521111597610.webp)