For a long time, movement has been regarded as an unqualified good. To leave was to grow; to travel was to expand one’s sense of the wider world; to cross borders was to gain perspective.

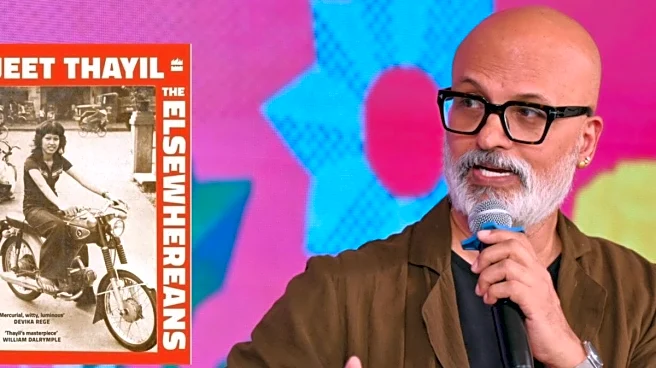

However, movement also stretches intimacy across distance, turns presence into something intermittent, and alters familial obligations. Jeet Thayil’s latest book explores this complex terrain — The Elsewhereans is not a celebration of mobility but an attempt to understand its emotional, ethical, and inherited repercussions.

Thayil’s book is, as its subtitle describes, “a documentary novel,” a concept that becomes clearer as one progresses through it. This is a family history crafted like a scrapbook, containing fragments, fictions, and collections: letters, photographs,

reconstructed dialogues, and archival materials, all revolving around his parents with him in the background.

Dedicated to his mother, who passed away earlier this year, the book aims to articulate a condition created by migration that we have struggled to name; not quite exile, not quite cosmopolitanism, but something Thayil calls being “Elsewherean”. It is a way of being formed across cities and continents, inherited as much as chosen, where belonging is distributed rather than anchored.

The narrative assembles itself through these fragments, leaving readers unsure of what truly happened and what has been shaped by the telling, and the author seems uninterested in clarifying that boundary. Early in the epigraph, he quotes Czesław Miłosz: “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.”

This serves both as a warning and methodology, since writing about family is not only remembering it but exposing it, and perhaps more uncomfortably, exposing how one has been shaped by it, revealing that personal choices are often inheritances.

The book populates itself with a diverse array of characters – a drug peddler in Germany, a tour guide in Vietnam, a Franciscan priest, and a woman unhappy in her marriage who dreams of travelling the world as an assistant to a blind tour guide – and for stretches in the middle, readers may not understand their presence or connections. New figures appear without much introduction, stories branch off unexpectedly, and the structure can feel loose.

This is deliberate rather than careless, almost as a metaphor for travelling and migration, which involves tangents, hiatuses, and periods of waiting. By the end, it becomes clear that despite its populated landscape, the book is essentially the story of one woman – Ammu, Thayil’s mother – seen through the lives that orbited her and the condition she embodied and eventually recognised in herself.

The book succeeds because Thayil neither romanticises the “Elsewherean” condition nor reduces it to loss. His parents are not static figures waiting while their son wanders. Their lives are marked by departures and failed returns, by attempts at settling that never quite succeeded.

At one point, after over half a century of migrations within and outside of India, when Ammu and George finally return to their chosen place – Kerala, the ancestral home they had imagined returning to for years – they discover that “Kerala has changed and they have too. There’s no sense of belonging or welcome. They’ve lived Elsewhere too long: they’ve become Elsewhereans”.

This realisation is particularly striking because Ammu, more than anyone in the family, maintained the strongest sense of being Malayali while living abroad: “She is a Malayali before she is a citizen of Elsewhere”, we are told early in the book. But the return reveals what distance had obscured: that being elsewhere changes not just where you are, but who you are. The place you left keeps moving without you, and upon your return, you meet as strangers who once knew each other well.

Thayil pays sustained attention to his mother’s interior life, which steadies the book when its structure loosens. Ammu is not reduced to a symbol of maternal sacrifice or waiting. She builds routines, orders her days, and constructs what the book calls “a republic of one” through sudoku puzzles – a space where “numbers are clean and true … and don’t change or make inexplicable decisions, unlike husbands and children whose actions are impossible to predict”.

One of the book’s most quietly devastating moments comes when Ammu considers calling her son back, given her husband – his father – has been diagnosed with cancer. “But what is the point?” she thinks, “he is too distracted to talk these days, a brown man wandering around strange foreign cities, much as his parents had once done”.

The hesitation carries multiple meanings. There’s the familiar guilt of the migrant son, but also something more complex: a recognition by the parents that the restlessness they observe is an inheritance, something they modelled.

When the author admits elsewhere that he was, for much of his life, a “bad son” now trying to make amends by being there for family, it reads less like confession than accounting. The restlessness he seeks to atone for is also the restlessness she taught him. “Elsewhereanness”, it turns out, is something you grow into long before you choose it.

The book does not limit the “Elsewherean” condition to the cosmopolitan class who travel by choice. Toward the end, Thayil expands the frame to include India’s internal migrants, particularly the increasing number of north Indian wage labourers in Kerala – people whose movement is driven not by curiosity or opportunity but by necessity. He notes the growing hostility towards them, the us-versus-them mentality that views their presence as intrusion rather than labour.

These figures are “Elsewhereans” too, though their condition lacks the romantic associations of international migration. They are viewed with suspicion, required to prove they belong, caught in the same dynamics of displacement without the privilege that softens it. Thayil doesn’t equate their experience with his own, which would be inappropriate, but he acknowledges the juxtaposition.

The incident in Palakkad this week – a migrant worker beaten to death on suspicion of theft – highlights what the book suggests: that Elsewhereanness exists on a spectrum, and for some, movement itself becomes grounds for violence.

The book returns to Ammu’s story in its closing movement, bringing everything together with unexpected grace. Relationships reappear and become clearer, and what seemed digressive in the middle suddenly appears deliberate. The effect is cumulative rather than climactic, fitting for a book more concerned with recognition than resolution.

In the end, Ammu’s death becomes the moment when the book’s method fully reveals itself. The author hints at death being akin to a river, the same river that runs by their ancestral home, the place she thought she had returned to but where she could never fully belong again. He disperses her ashes there, acknowledging that the “Elsewherean” condition doesn’t end with going back; perhaps it doesn’t end at all; the river keeps moving regardless.

Ultimately, Thayil offers vocabulary. The “Elsewherean” isn’t someone without roots but someone whose roots are distributed – across people, memories, incomplete journeys, cities and countries, and rooms in flats in those cities.

It’s a useful term for a condition many recognise but struggle to name, one transmitted through families long before it’s understood or chosen. Next time someone asks where I’m from, I might resist listing countries or constructing a chronology and simply say: I am an Elsewherean, from elsewhere.

(Nishad Sanzagiri is a writer and consultant based between London and Goa. A graduate of the universities of Edinburgh and Oxford, his writing in ‘Infinity Inklings’ explores memory, identity, travel, and the diasporic gaze. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177082860764063168.webp)

/images/ppid_a911dc6a-image-177082857077520752.webp)