War is often described through images of destroyed buildings, injured bodies, and displaced populations. What receives far less attention is the quieter and more enduring damage done to children’s emotional

worlds. Armed conflict disrupts the foundations of childhood itself: safety, routine, care, learning, and play. For children growing up in war-affected regions, fear is not an occasional experience but a constant condition of life.

“Terrible things are happening outside. Poor helpless people are being dragged out of their homes. Families are torn apart. Men, women, and children are separated. Children come home from school to find that their parents have disappeared.” These words were written by Anne Frank in January 1943 during the Second World War. Decades later, they continue to describe the lives of millions of children in places such as Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, Syria, and Myanmar. The settings have changed, but the emotional burden placed on children has not.

While armed conflict leaves visible scars on cities and communities, its emotional impact on children often remains unseen and unaddressed. These effects are not temporary. Emotional distress experienced during childhood can shape development and continue to influence mental health, relationships, and self-perception well into adulthood.

Childhood is generally associated with protection, stability, and growth. Conflict breaks these basic conditions. Children in war zones are exposed to bombings, forced displacement, separation from family members, the loss of loved ones, and the destruction of homes and schools. According to UNICEF, millions of children worldwide grow up in environments where violence and insecurity are a daily reality rather than an exception. In such circumstances, children rarely have the space or support to process grief as it occurs. Fear and loss are often internalised, remaining unresolved and resurfacing later in life in different emotional and psychological forms.

Judith Herman’s work on trauma helps explain this process. She argues that trauma damages a person’s fundamental sense of safety and trust in the world. For children, whose emotional and social understanding is still developing, this rupture can be especially deep. When violence becomes routine, adults and institutions no longer appear as reliable sources of protection. Safety begins to feel uncertain and temporary. Over time, this alters how children relate to others and how they imagine their future.

One of the most common psychological consequences of prolonged conflict is toxic stress. This refers to long-term exposure to fear and instability without adequate emotional support. Research shows that children exposed to war frequently experience anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, and difficulty concentrating. Some develop symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. As Bessel van der Kolk has shown, trauma is not experienced only through memory or thought. It is also carried in the body, shaping stress responses, emotional regulation, and behaviour. These reactions are not signs of weakness but normal responses to deeply abnormal conditions.

Children do not all respond to trauma in the same way. Early research by Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham during the Second World War demonstrated that younger children often regress under stress. They may become unusually dependent on caregivers, lose language or social skills they had already acquired, or experience bed-wetting. Older children and adolescents may withdraw emotionally, express anger, or engage in risky behaviour. Many children also experience guilt, believing they are responsible for their family’s suffering, even when this is not true. Such beliefs can quietly undermine emotional wellbeing and self-esteem.

Emotional harm is not caused only by direct exposure to violence. Ongoing uncertainty, repeated displacement, and the constant fear of losing loved ones place children in a state of continuous alertness. Life in refugee camps or temporary shelters often involves overcrowding, lack of privacy, and disrupted routines. Education is frequently interrupted. UNHCR reports show that displacement often lasts for years, transforming emergency situations into long-term childhood environments. The absence of stability deepens emotional insecurity and stress.

Loss is another defining feature of childhood in conflict zones. Children may lose parents, siblings, friends, homes, and entire communities. Yet children often lack the language, emotional vocabulary, and social permission to express grief openly. When loss is not acknowledged or supported, grief does not disappear. As Veena Das has shown in her work on everyday violence, suffering often becomes woven into ordinary life rather than resolved. For children, unresolved grief can shape emotional health, relationships, and self-esteem well into adulthood.

In long-running conflicts, some children grow up knowing nothing but war. Research from conflict-affected regions shows that constant exposure to violence can normalise fear. Hope, imagination, and long-term planning may give way to survival, mistrust, and emotional numbing. When violence becomes ordinary, it reshapes children’s understanding of relationships, society, and the future.

Education plays a crucial role in supporting children’s emotional wellbeing. Schools provide routine, structure, and a sense of normal life. Even temporary learning spaces in refugee settings can help children feel connected and supported. However, when schools are damaged, occupied, or attacked, education itself becomes a source of trauma. Attacks on schools and teachers send a powerful message that even spaces meant for safety are not protected. The loss of education also limits future opportunities, increasing long-term emotional stress.

Despite these conditions, children in conflict zones are not only victims. Many demonstrate remarkable resilience. Research by Catherine Panter-Brick and Michael Wessells shows that supportive relationships play a central role in helping children cope with trauma. Care from parents, caregivers, teachers, and peers can reduce emotional harm. Cultural practices, storytelling, play, and community support help children make sense of their experiences and restore a sense of belonging.

Psychologists emphasise that resilience does not arise from individual strength alone. It depends on social and emotional support systems. Children cope better when they have at least one stable and caring adult and when their emotions are recognised and taken seriously. Trauma-sensitive education, play therapy, art-based activities, and group discussions have been shown to help children process fear and loss in constructive ways.

There is growing recognition of the need for mental health and psychosocial support in conflict settings. However, such services remain limited and underfunded. Emotional wellbeing is often treated as secondary to food, shelter, and medical aid. This neglect is short-sighted. Emotional harm can persist long after physical danger has ended and may affect not only individuals but entire societies across generations.

Anne Frank’s diary reminds us that the emotional suffering of children during war is not new. What has changed is the scale of conflict and the number of children affected. Protecting children in conflict zones requires attention not only to their physical survival but also to their emotional lives. If emotional wounds are ignored, societies risk raising generations shaped by fear and unresolved trauma. Supporting children’s emotional wellbeing is essential for recovery, peace, and a more stable future.

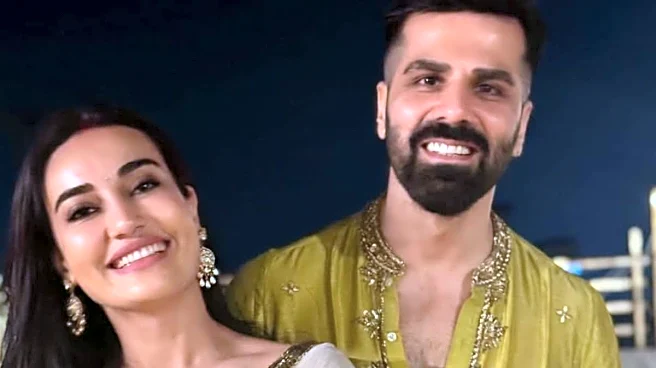

Vaishali Sharma is a Master’s student in History at the University of Delhi, passionate about inclusive and holistic education. Her research interests include education, public policy, and international relations, with published works on curriculum. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.