What's Happening?

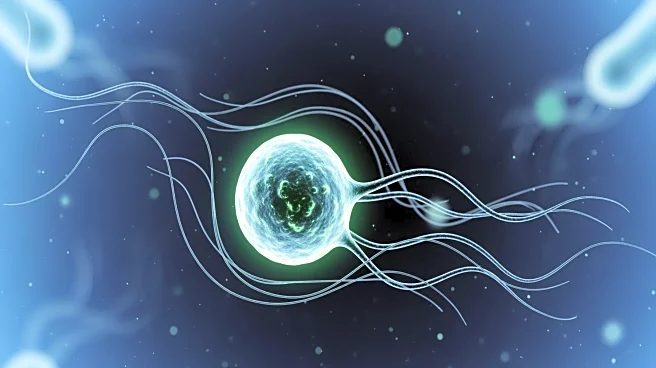

Researchers at the Flatiron Institute have proposed a new explanation for how bacteria swim, challenging the long-held 'domino effect' model. The study, led by Henry Mattingly and Yuhai Tu, suggests that bacterial flagella switch their rotational direction

through a process called 'global mechanical coupling.' This mechanism involves an active tug-of-war among distant proteins, rather than passive pressure from neighboring proteins. The flagellar motor, composed of 34 proteins, is influenced by the molecule CheY-P, which affects the direction of rotation based on environmental signals. The new model explains the energy-driven, cooperative nature of the switching process, which was not accounted for in previous equilibrium-based theories.

Why It's Important?

This discovery provides a deeper understanding of one of biology's most studied molecular machines, the bacterial flagellar motor. By revealing the active role of stators in direction switching, the research challenges existing models and offers insights into nonequilibrium systems in living organisms. Understanding bacterial motility at this level could have implications for various fields, including microbiology, bioengineering, and the development of antibacterial strategies. The findings may also inform research on more complex biological systems, as the principles of energy dissipation and cooperative behavior are fundamental to many biological processes.

What's Next?

The researchers plan to refine their model by integrating more experimental data to better match observed behaviors. This could lead to further insights into bacterial chemotaxis and other nonequilibrium biological systems. The study's findings may inspire new research into the mechanics of cellular processes and the development of technologies that mimic or manipulate bacterial motility. As the model is tested and validated, it could influence the design of synthetic biological systems and contribute to advancements in biotechnology and medicine.