What's Happening?

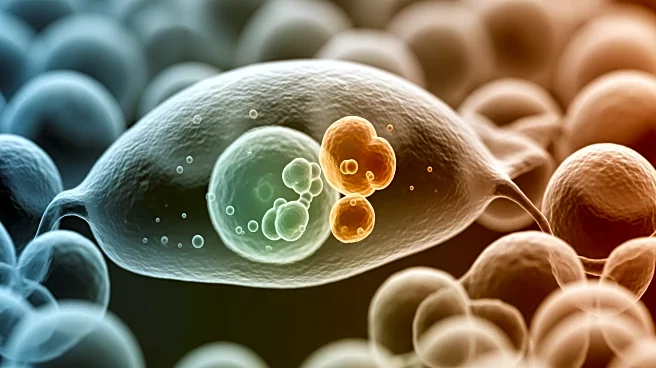

Recent research conducted by Professor David Suter and his team at EPFL's School of Life Sciences has uncovered a mechanism by which mammalian cells balance protein production and removal, termed 'Passive

Adaptation'. This study, published in Cell Systems, reveals that cells adjust their protein elimination rates in response to changes in protein synthesis rates. The researchers used a fluorescent protein to track protein production and removal in real-time, discovering that when protein synthesis decreases, cells reduce the components of their degradation machinery, thereby slowing protein elimination. This adaptation helps maintain stable protein levels despite fluctuations in resources such as amino acids or cellular capacity to build proteins.

Why It's Important?

The findings of this study have significant implications for understanding cellular resilience and stability, particularly in fluctuating environments. By elucidating how cells maintain protein balance, this research could inform future studies on cellular responses to stress, nutrient availability, and developmental changes. The discovery of passive adaptation provides insights into how cells protect themselves from potential damage due to protein imbalances, which is crucial for maintaining cellular health and function. Additionally, understanding this mechanism could have broader applications in biotechnology and medicine, particularly in developing strategies to manipulate protein levels in cells for therapeutic purposes.

What's Next?

Future research may focus on exploring the passive adaptation mechanism in different cell types and under various environmental conditions. There is potential for investigating how this mechanism can be leveraged in medical and biotechnological applications, such as improving cell resilience in tissue engineering or developing treatments for diseases related to protein misfolding and aggregation. Further studies could also examine the role of passive adaptation in embryonic development and its implications for reproductive technologies like in vitro fertilization.

Beyond the Headlines

The study also highlights the unique behavior of mouse embryonic stem cells, which activate a nutrient-sensing pathway called mTOR to maintain protein levels when synthesis rates drop. This additional layer of protection may be crucial for embryonic cells in harsh conditions, offering insights into early developmental resilience. Understanding these mechanisms could provide valuable information for improving the success rates of assisted reproductive technologies and enhancing our knowledge of early embryonic development.