What's Happening?

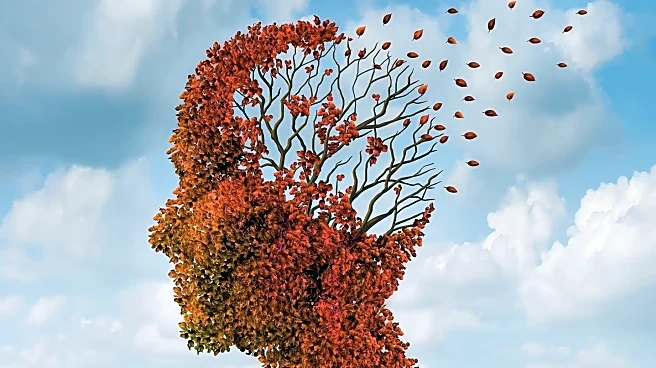

A recent study conducted by researchers at Karolinska Institutet has found a significant link between poor sleep and accelerated brain aging. The study, published in eBioMedicine, involved 27,500 middle-aged and older participants from the UK Biobank. Using MRI scans and machine learning, the researchers estimated the biological age of the brain and found that poor sleep could make the brain appear older than its chronological age. Participants' sleep quality was assessed based on factors such as sleep duration, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness. The study revealed that for every 1-point decrease in healthy sleep score, the gap between brain age and chronological age widened by about six months. The research also highlighted low-grade inflammation as a potential mechanism linking poor sleep to older brain age.

Why It's Important?

The findings of this study are significant as they suggest that poor sleep may contribute to accelerated brain aging, which is a risk factor for dementia. This has important implications for public health, as it highlights the potential for sleep interventions to prevent cognitive decline. Given that sleep is a modifiable behavior, improving sleep quality could be a viable strategy to mitigate the risk of dementia and other age-related cognitive impairments. The study also underscores the importance of addressing sleep issues as part of a comprehensive approach to maintaining brain health in aging populations.

What's Next?

Future research could focus on exploring interventions that improve sleep quality and examining their effects on brain aging and cognitive health. Additionally, further studies are needed to understand the underlying mechanisms linking poor sleep to brain aging, such as the role of inflammation and cardiovascular health. Policymakers and healthcare providers may consider integrating sleep health into public health strategies to address the growing burden of dementia and cognitive decline in aging populations.

Beyond the Headlines

The study's reliance on self-reported sleep data and its focus on a healthier-than-average population may limit the generalizability of the findings. However, the research provides a foundation for further exploration into how sleep affects brain health. It also raises ethical considerations regarding the accessibility of sleep health resources and the need for equitable healthcare interventions to address sleep-related health disparities.