Turbocharged engines can be great at boosting performance and efficiency, but in life, as in economics, there's no such thing as a free lunch. In other words, benefits like those come with a cost, whether

it's turbo lag — which you can't really fix — or the actual cost of more frequent oil changes. Because not only do turbo engines need different oil from naturally aspirated motors, but they also need to have it replaced more often.

It's a fact of life that more and more people are learning, too, since turbochargers are becoming more popular than ever in the auto industry. That may seem a little counterintuitive with the push toward electrified vehicles, but the two really go hand in hand. Hybrids, plug-in hybrids, and extended-range plug-ins all pair internal combustion engines with electric power. And for fuel-efficiency purposes, the trend is to shrink the engine size but make up for its smaller displacement with turbocharging and electricity.

To let you know how fast the turbo market is growing, only about 1% of new cars sold in the U.S. in 2000 had one, but 23 years later, that mark had jumped to 37%. Today, some analysts say that's increased to 50%. That's a lot of turbocharged engines needing a lot of oil, so let's find out what's going on here.

Read more: Save Your Engine: 5 Tips For Preventing And Cleaning Carbon Buildup

The History Of Turbochargers And How They Work

One of the best ways to understand why turbocharged engines need more frequent oil changes is to understand how they work. The concept was patented back in 1905 by a Swiss engineer named Alfred Buchi. But it took Buchi another 20 years to successfully implement the technology. And turbocharging was initially used in ships and aircraft, not automobiles.

This changed in 1954, when Volvo and MAN introduced the first production trucks with turbos. Turbocharging production cars got its start in 1962, when Oldsmobile introduced the JetFire V8 for its iconic Cutlass. The modern era of turbo performance, however, began in the mid-1970s as automakers tried to balance power and fuel economy during the oil crisis caused by the OPEC embargo. This is when forced induction found its way into legends like the Porsche 911 Turbo that helped the company celebrate 50 years of turbocharging last year.

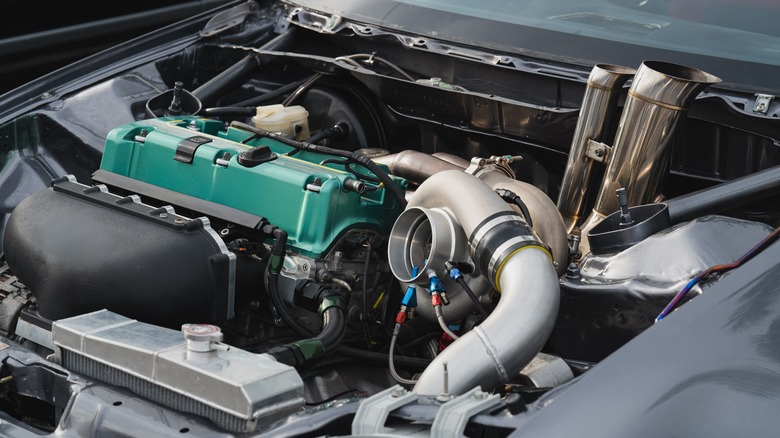

In all of these vehicles, the way the turbocharger operates is that exhaust gas from the engine is used to spin a small fan-like part called the turbine wheel. It's attached by shaft to a similar component called the impeller, or compressor wheel. The exhaust gas spins the turbine, which spins the impeller, which helps suck in extra air and force it into the cylinders to enhance combustion. (Usually, turbos also have an intercooler to lower the temperature of the fresh air, making it denser and thus letting it contain more air molecules.)

Why Do Turbocharged Engines Go Through Oil So Quickly?

Turbochargers work hard to deliver higher performance, with the turbine/impeller spinning up to 350,000 times a minute. To put that into context, the redline for the Ferrari LaFerrari — considered one of the highest-revving street cars ever — is 9,250 rpm. The incredible speed of the turbo wheels is exacerbated by the heat they have to endure, especially the turbine wheel that's facing extremely hot exhaust gas. As a result, the turbine manifold can reach temperatures of 600 to 950 degrees Celsius (1,112 to 1,742 degree Fahrenheit). That can be hot enough to melt silver.

Meanwhile, excess heat is a deadly enemy to oil performance. High temperatures lead to thinner oil, preventing proper lubrication, and if the oil gets hot enough, it can start to break down. The extreme heat of turbochargers is especially problematic since the temperatures can get high enough for "coking," the creation of coke deposits on the turbo components. The point being, turbocharged engines put oil under much more stress than typical motors, causing it to degrade quicker. The only cure? Fresh oil.

Want more like this? Join the Jalopnik newsletter to get the latest auto news sent straight to your inbox...

Read the original article on Jalopnik.