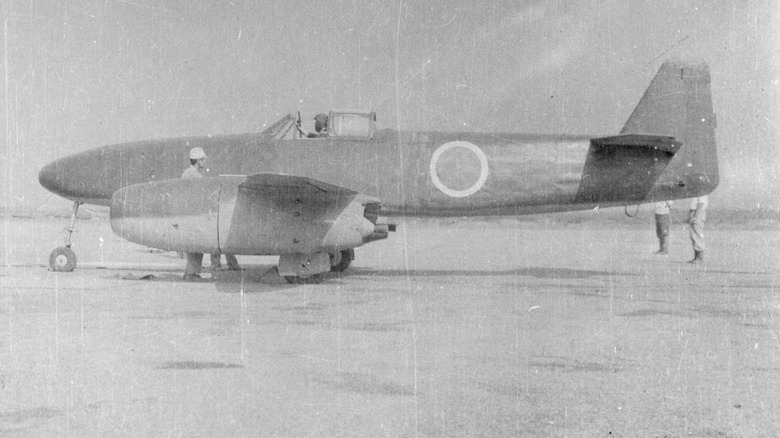

The Nakajima Kikka ("Orange Blossom") was Japan's first turbojet (not to be confused with turbofan) aircraft, developed in 1944–45 as the Pacific War turned against Japan. Inspired by Germany's failed

Messerschmitt Me 262, which Japanese officials had seen demonstrated during a 1942 visit, the Imperial Japanese Navy ordered Nakajima to design a compact, twin-engine attack jet. It needed to be easy to manufacture by unskilled labor and small enough to store in tunnels or caves to protect it from Allied air raids. Folding wings were specified for this reason.

The project was led by Kazuo Ohno and Kenichi Matsumura. While it looked similar to the Me 262, the Kikka was smaller and featured straight wings instead of the German jet's swept design. Initial concepts called for it to be a single-use kamikaze aircraft with no landing gear, carrying a single bomb. Early engine plans involved the Tsu-11 and Ne-12, but these lacked the required thrust. Japanese engineers, working from several photographs of Germany's BMW 003 turbojet brought back by Commander Eiichi Iwaya, reverse-engineered the Ishikawajima Ne-20 axial-flow turbojet, producing about 1,047 pounds of thrust.

The final Navy requirement called for a top speed of around 430 mph, a range of between 200 and 270 km depending on bomb load, and a takeoff run of 350 meters with rocket assistance. Armament plans for operational models included either a 500 kg or 800 kg bomb, or twin 30 mm Type 5 cannons for an interceptor version.

Read more: 10 Largest Air Forces In The World, Ranked By Military Aircraft Numbers

Flight Testing And Performance

By mid-1945, Japan's industrial situation was dire, with air raids disrupting production and dispersing assembly to rural sites. The first Kikka prototype was completed by late July 1945 and moved to Kisarazu Naval Air Base for trials. On August 7, 1945 (one day after the Hiroshima bombing), Lieutenant Commander Susumu Takaoka piloted the Kikka on its first flight. The test lasted around 11 minutes. The jet reached about 195 mph at 11,000 rpm while staying low over Tokyo Bay with landing gear extended. Takaoka found the controls mostly effective, though the elevator was sensitive and the rudder and ailerons heavy. Fuel consumption was high, and he noted engine throttle lag and a risk of flameout below 6,000 rpm.

Four days later, on August 11, a second flight attempt used rocket-assisted takeoff (RATO) units. These had been mounted at the wrong angle, causing an immediate and extreme nose-up pitch on ignition. With visibility lost and speed dropping, Takaoka aborted the takeoff. The aircraft overshot the runway, crossed a grassy area and trench, and came to rest in shallow water, damaging its engines and landing gear. The incident ended further testing.

A second prototype, intended to fly soon after, was nearly complete when Japan surrendered on August 15. Around 25 unfinished airframes were found in Nakajima factories. Plans also existed for reconnaissance versions and upgraded interceptors with more powerful Ne-20 engines. Despite its promise, the Kikka had no chance to prove itself in operational service.

Fate And Legacy

After the war, U.S. forces discovered incomplete Kikka airframes and Ne-20 engines in Japan. One was shipped to the United States for evaluation at Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland. Engineers also sent Ne-20 engines to the Chrysler Corporation, which built a working example from parts and tested it for almost 12 hours. However, U.S. jet technology had already surpassed Japan's late-war designs, and the Kikka was never flown in America.

Two surviving airframes are preserved by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. One is displayed at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, missing its engines. The second remains in storage. Other Ne-20 turbojets survive at the Tokyo National Science Museum, Japan's IHI (Ishikawajima-Harima) company museum, and the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

Though it arrived too late to influence the outcome, the Kikka remains a significant milestone in Japanese aviation history. It marked the nation's entry into the jet age of aviation under extraordinarily difficult circumstances and stands today as a rare example of wartime innovation forced to maturity in the final days of conflict.

Want the latest in tech and auto trends? Subscribe to our free newsletter for the latest headlines, expert guides, and how-to tips, one email at a time.

Read the original article on SlashGear.